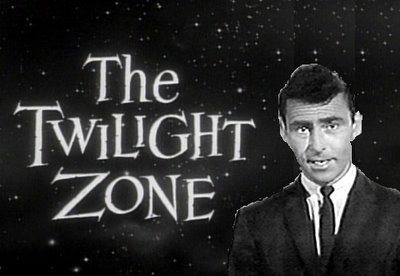

This Rod Serling brainchild was unlike any other program that came before it.

Nick Krewen

Music, Sun., April 10, 2016

The Twilight Zone

Childhood rating:

Adult rating:

Four stars.

An innovative CBS TV series created and hosted by Rod Serling that ran between 1959 and 1964, and has been revived three times since — once as a feature film in 1983, and twice as a series in 1985 and 2002.

When Earl Hamner Jr. died on March 24, the final writing connection of a legendary and groundbreaking TV series perished with him.

I’m not referring to his nine-year run of The Waltons, the 1972 rural semi-autobiographical family drama that Hamner created and was notorious for ending each broadcast with the 11-member clan annoyingly bidding “good night” to one another. No, it’s the episodic program where he got his first big break as a TV writer that floats my boat: The Twilight Zone.

Filmed in glorious black-and-white and filled with taut, mind-bending scripts, this Rod Serling brainchild was unlike any other program that came before it, changing the dynamic of network television by tearing open the portals of the imagination. Over the course of five seasons and 156 episodes from 1959 through 1964 (92 of which were penned by the series architect himself), the Syracuse-born future Planet of the Apes co-author presented sci-fi steeped tales that usually ended with a significant twist the viewer didn’t see coming.

Rod Serling

How can you forget the weekly intro, supplied with Serling’s inimitably charismatic baritone: “You’re travelling through another dimension, to not only of sight and sound, but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. Your next stop: The Twilight Zone.”

Admittedly, the series debuted before I took up residence in my mother’s womb, although one of my earliest TV memories was a rerun episode, “To Serve Man” (“Mr. Chambers, don’t get on that ship! The rest of To Serve Man — it’s a cookbook!”) The scary-looking nine-foot-aliens called the Kanamits kept my 4-year-old brain awake for days.

Recently, I purchased the box set to see how well the series stacked up 56 years later, and the answer is … remarkably! Granted, the post-World-War-II era in which The Twilight Zone was filmed was a polite one, where everyone was addressed as “Sir,” “Miss,” “Mr.” and “Mrs.” and you could buy a cup of coffee for a dime and a beer for 86 cents.

But the observations and lessons that accompanied each 30-minute parable (stretched to 60 minutes for its 18-episode fourth season) remain pretty well applicable today: a man/woman yearning for something unattainable and realizing it’s not quite what he/she anticipated it to be once they get it; how human avarice leads to regretful decisions, even if the supernatural might be involved; and how hope is often the closest step to, or from, tragedy.

Serling employed his weekly platform as a mirror, and his Emmy-winning knack for forcing viewers into contemplation was incentive enough to tune into the show, not to mention a menagerie of future TV and film stars (William Shatner, Jack Klugman, Julie Newmar, Elizabeth Montgomery, Robert Redford, Charles Bronson), that showcased their formidable talents. Horror, humour, wonder, shock, the strange and the familiar were meted out in equal dollops on Serling’s intellectual panorama.

The Hamner Jr. connection? Selling and he met at an awards ceremony in 1948. Hamner was hired for the 1962 episode “The Hunt” and authored eight more, including the original series finale, 1964’s “The Bewitchin’ Pool:” credits that are way cooler than those Waltons miscreants.

A look back at what made The Twilight Zone so great | Toronto Star

Here are five exceptional Twilight Zone episodes:

“Once Upon A Time” (1961) An ingenious and lighthearted tribute to Buster Keaton written by Richard Matheson, the show begins as a silent film as grumpy janitor Woodrow Mulligan (Keaton, 65 at the time) accidentally transports himself trouserless from 1890 into the future via a Time Helmet. When he reaches 1960, the episode turns into a “talkie” as he meets a scientist (Stanley Adams) with ulterior motives to help him get back home. When he returns to his original time, the episode reverts back to silence.

“Time Enough at Last” (1959) Starring Burgess Meredith as Harry Bemis, a nebbish bank teller whose love of books outweighs his take on reality. During his lunch hour, he steals away to his vault to read and is knocked out by an explosion. Coming to, he is the last survivor on Earth, discovers a library, but falls and breaks his glasses just as he’s about to start his first book.

“Mr. Dingle, the Strong” (1961) Another Burgess Meredith episode, with the character, vacuum-cleaner salesman Luther Dingle, given superhuman strength by an invisible two-headed Martian scientist as an experiment. Disappointed by Dingle’s propensity for publicity, the Martian removes his powers just in time for the salesman to embarrass himself on national TV, and give him to the Venusians, who imbibe him with superintelligence.

“The Silence” (1961) Archie Taylor (Franchot Tone) hates the sound of Jamie Tennyson’s voice, and makes the heavily-in-debt Tennyson (Liam Sullivan) a bet: if he will remain silent for one year, Taylor will pay him $50,000. Tennyson wins the bet, but when it comes time to settle, Taylor announces that he’s broke. Tennyson reveals his own trump: he had his vocal cords severed. Serling at his finest.

“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” (1963) William Shatner plays Bob Wilson, a man recovering from a nervous breakdown seated in a plane and who, midflight, sees a creature outside his window trying to disable the wing. Unfortunately, nobody sees it forcing Wilson to take matters into his own hands. Even though authorities are waiting for him with a straitjacket once the plane lands, Wilson is confident he’ll be exonerated, as the final scene focuses on the physical damage done to the wing. One of the most popular TZ episodes.

Be the first to comment on "A look back at what made The Twilight Zone so great"