June 02, 2014

Nick Krewen

GRAMMY.com

When aging actors and actresses need a sip from the fountain of youth to sustain their Hollywood dreams, they call their plastic surgeons for a little nip n’ tuck.

But when record companies or artists need to revitalize a classic album and freshen up its sound, it’s the mastering engineer who is the expert on their speed-dial, specifically for remastering purposes.

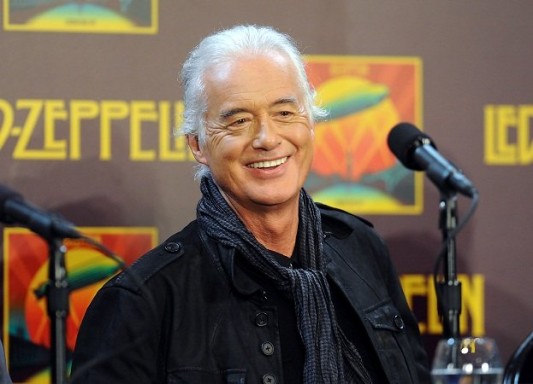

It’s a popular practice, highlighted over the past year with the re-release of the nine-album Led Zeppelin catalogue, overseen by Jimmy Page, as well as both vintage and contemporary titles revived and rejuvenated by the 75th anniversary of Manhattan’s Blue Note Records.

Jimmy Page photo by Avda via Creative Commons

In fact, anniversaries seem to be as good excuse as any to revisit some old classics: those undergoing the sonic knife over the past 15 months include Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road; Soundgarden’s Superunknown; Stan Getz/Joao Gilberto’s Getz/Gilberto; Bachman-Turner Overdrive’s Not Fragile; Eric Clapton’s 461 Ocean Boulevard, There’s One In Every Crowd and E.C. Was Here; The Who’s Tommy; Prince’s Purple Rain, Bryan Adams’ Reckless and Bon Jovi’s New Jersey.

The retooling process also extends to catalogues as well, as noted by last year’s 16-disc compilation Joe Satriani, The Complete Recordings and the ongoing Blue Note series presided over by label president Don Was that commenced almost a year ago with the March 25, 2014 reissues of Art Blakey’s Free For All, Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil, John Coltrane’s Blue Train, Eric Dolphy’s Out To Lunch and Larry Young’s Unity.

Some of those key titles not only arguably sound better, but are enhanced by such bonus fare as previously unreleased material, alternate takes, live performances and other extras designed to make fans salivate and hopefully reach into their wallets to buy an album they already have in one, two or three configurations.

But first and foremost, it’s about better sound for today’s technology. With advances in both the music industry and recording fields, ranging from studio equipment to the evolution of formats that began with vinyl and analog tape and have shifted to digital options that include the MP3, MP4, AAC, WAV, AIFF, FLAC and DSD/DFF, as well as bit-rates that have jumped from 16 to 24, via computer and Internet, it’s no wonder Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page felt compelled to revisit his band’s 200-million-plus selling discography.

“It (mastering) was done for vinyl, back in the ’60s and ’70s, and then 20 years ago it was redone and remastered for CD,” explained Page at the New York press conference last May to promote the revamped catalogue.

“Now we’ve got so many different formats out there that it made sense to revisit the studio albums and do those.”

Page, who personally remastered each of his band’s nine studio albums and converted them into 24-bit hi-definition files, says he wasn’t thrilled with previous remasters.

“CDs were put out of that material from copy tapes, and they weren’t very good, to be honest with you, so that’s why the original master tapes were brought back out again and remastered,” says Page, 71.

“That was 20 years ago, so [now] you’ve got all the new digital formats that there are. The process has changed as far as mastering because now you’ve got other areas and elements to fill. Even with the remastering and cutting on vinyl, there have been so many steps and progressions to improve the overall (sound), if you like.”

Even before they get started, engineers can face daunting obstacles – missing, misplaced or destroyed tapes; some types of audiotape where they’ve become worn or decayed over the years, forcing engineers to try to physically repair the original master.

Ironically, while sourcing through materials that are over 45 years old, tape degradation was the one thing Jimmy Page didn’t have to worry about.

“The condition of it was absolutely magnificent, “ Page enthuses. “I didn’t have to do any sort of restoration work on that, apart from maybe a little edit might come out and you’d replace the editing tape. However, the In Through The Out Door album had been recorded on this new format tape — and you’ve probably heard about tape shredding and all of that, which means the oxide comes off and you have to bake them– so fortunately there wasn’t a lot of work that needed to be done past In Through The Out Door.”

Arguably, some titles have had their sound spruced up to the point of overkill – take Pink Floyd’s classic Dark Side Of The Moon, for example; a work which has undergone the process no less than a handful of times.

Why?

“Record companies remaster to try to get more money out of the catalogue to turn the catalogue, and thus, the artist as well,” surmises veteran mastering engineer Bob Ludwig, a seven-time GRAMMY winner who has won for his work with Daft Punk and Mumford & Sons on 2013’s and 2012’s Album of the Year, Random Access Memories and Babel, respectively. “I don’t think there’s that many titles where the fans are begging the artist to redo it.”

Bob Ludwig

photo credit – Peter Leuhr

But Ludwig, who is based in Portland, Maine, owns Gateway Mastering, and counts such multi-million sellers as Led Zeppelin II and Houses Of The Holy; Dire Straits’ Money For Nothing and AC/DC’s Back In Black as some of the 1300-plus titles he’s mastered since 1969, allows for exceptions.

“I’ve just remastered most of the early Bruce Springsteen catalogue for iTunes, and the first two titles, Greetings From Asbury Park and The Wild. The Innocent And The E Street Shuffle, fans had been asking for those for quite awhile.

“Those were originally done when CDs first came out – I did the original U.S. masters of those CDs in ’84, but they were made in Japan and done from the analog cassette copy masters.”

Ludwig says improved technology has made remastering more appealing.

“The quality of (analog-to-digital) converters that we use now is so much better than the early digital converters,” states Ludwig. “And there’s so much gear that’s been invented.”

In turn, better equipment, both at the source end and what you hear through the speakers, promotes a greater accuracy in the mix.

“When you create the final master, the idea is to make it sound as good as it can possibly be sounding over an excellent system,” says Ludwig. “The more accurate you make it, and the more accurate it sounds on an excellent system, the better it sounds on a wider range of things out there in the world.”

Another reason for aurally revisiting a catalogue may be artist preference, says John Cuniberti, who spent two years remastering the 16-disc set Joe Satriani: The Complete Studio Recordings. He says sometimes it’s just the benefit of hindsight that serves as a remastering catalyst.

“A lot of times the artist might wish the mastering might have been done differently,” says Cuniberti, a Grammy winner who has mastered albums for Dave Matthews, Aerosmith, Tracy Chapman and The Grateful Dead. “Sometimes when you lead a mixing project and it goes right to master because you have a deadline to meet, it’s really hard sometimes to be objective about the mastering process. You’re pretty burned out on it. You don’t even want to hear it, generally. “

He chuckles.

“In fact, that’s one of the reasons why you turn it over to a mastering engineer is a good idea after you’ve spent weeks or months mixing so they can provide that service. It’s so they will have an objective ear. So if you’ve lived with your record for 10 years, you might go, ‘maybe we can try something different.’”

In Satriani’s case, where different mastering engineers handled his albums over the years, Cuniberti says the timing to offer one cohesive sonic overview was never better.

”When we first started having the conversation about remastering, I said, ‘We have an opportunity here that we’re not ever going to have again: to present the entire catalogue and remaster it as one whole piece rather than just giving people the already mastered discs in a box,’” Cuniberti recalls.

“We can create a consistency in level and quality right from the first record.”

Cuniberti says Satriani’s recorded career overview was also a chance to rectify an embarrassing development in the history of remastered recordings: The Loudness Wars.

“Over the past 15-20 years, the (44.1/16-bit) CD has been getting louder and louder,” Cuniberti explains. “This has been largely due to the necessity to stand out amongst the crowd. Originally, the record companies were encouraging it. The artists, maybe their egos got in the way, and they wanted their record to be at least as loud as so-and-so’s, and so-and-so needed to make their record a little louder, and it produced what we call the ‘Loudness Wars.’

“The audio quality and the sound of the mix ultimately would suffer from that process.

“Now we have the opportunity to go and back off some of the limiting and processing that was taking place to fight that war, and really look at the album more aesthetically.”

Gavin Lurssen of Hollywood-based Lurssen Mastering notes that delivering the right sense of nostalgia as a remastering engineer is something that should also be taken into account, as it takes great skill.

“When you’re living in 2014, we have mobile devices and electronic billboards and all kinds of crazy information entering our brains at light speed,” says Lurssen, who mastered 2001 Album of the Year GRAMMY winner O Brother Where Art Thou? and 2008’s similarly rewarded Raising Sand by Alison Krauss and Robert Plant. “But there’s always, as in the case in human nature, an ability and a desire to reminisce.

Gavin Lurssen

“So when you present something to somebody that was once a part of their lives, in some kind of cleaned-up fashion, you have to present it to them in a way that makes it feel like it felt back at that time, and combine it also to some degree — dependent on the vintage of the project — with the standards of today in order to create that feeling.

“Generally there is a lot more dynamic range on older recordings so it is important to respect that and thus the level wars are less of an issue in this line of work, “ Lurssen adds. “I’ve even seen cases in which this approach has helped pull current artists out of the overall level push when they see what can come of it. It’s all about being exposed to it, which is among the good reasons the labels are doing it.”

Barak Moffitt, Universal Music’s Head Of Strategic Operations, and the executive who oversees Capitol Studios and Mastering, says the respect that Lurssen mentions is tantamount to the Blue Note 75th Anniversary Remastering project.

Barak Moffitt

“We’re trying to get a balance between what’s directly on the tape and what happened in that room, and the emotional connection that people found in that original vinyl release, where the public sentiment and the original sentiment around the music was attached,” he explains.

“And again, now that studio technology has hi-definition capabilities, we’re taking care to maintain as much information that’s in the original material as possible, while maintaining as much of the emotional connection to the original release as possible.”

Moffitt says that also involved preserving the integrity of the original masters wherever possible; a task the label took extremely seriously.

“Our first concern was to respect our responsibility as stewards of these original masters,” Moffitt explains. “So we developed what we call sort of these white-glove protocols around our tape-handling procedures, and how we manage the actual physical assets in and out of the vaults.

“We also wanted to make sure that throughout the two-stage process –retrieving the actual analogue assets from the vault, and then transferring them into the digital world in hi-definition for historical preservation – we took great care to preserve as much information that’s in the analog domain in the digital space as possible, given current studio technologies.

“We also took great care to engineer our signal processing chain, all the way from what kind of power cables we were using to what analog-to-digital converters we were using to the tape machines, the kind of software we were using, again with sort of the aim of maintaining the highest fidelity possible given today’s studio technology capabilities in the transfer from analog into the digital domain.”

From there, Moffitt says the results were then placed in the very capable hands of Bernie Grundman and his staff of Scott Sedillo and Beno May for both digital and vinyl purposes.

Of course, before an album can be remastered, it has to be mastered, a process that three-time GRAMMY winner and Blue Note Records president Don Was describes as “frosting on the cake.”

Don Was

“Musicians and engineers spend a whole lot of time getting the cake right, but most people don’t want to be served cake without the frosting on it,” he laughs. “But it’s a question of degrees of the frosting. You’ve got to have a light hand, basically.

“If you have something that’s badly recorded and mixed, a mastering engineer can come in and give it shape and dimension and depth by adding EQ and compression and other mojo to it, making sure the levels work and the spacing between songs is right — and then getting it into the medium from which it can be manufactured.”

Was maintains that like every musician and producer that works on an album, the mastering engineer leaves his unique fingerprint on the recording as well.

“Every mastering engineer has got their own gear and set-up, and that set-up has a sound to it.”

And that introduces another challenge: maintaining the integrity of the original mastering engineer’s work.

“Let’s take the Blue Note remasters for example: Rudy Van Gelder, the legendary engineer who recorded most of the classic Blue Note Records, mixed directly to stereo on quarter-inch tape,” Was explains. “There was no multi-track tape, so he mixed live. So the music went down and it came out mono or stereo and that was it – there was no going back to remix it.

Blue Note Records’ Rudy Van Gelder

“He also mastered, and the way he mastered that day has a certain quality to it and it’s definitely different from when you hear what’s on the master tape.”

When it came to the initial listens of remastered works that had been converted to hi-def and transferred to digital at the 96k/24-bit and 192 k/24-bit rates, Was noticed that the music felt different than how he remembered it.

Was says Van Gelder pre-emptively mastered the record for vinyl to ensure there would be no technical glitches when consumers played them on their home audio equipment.

“Rudy mastered for vinyl: he added some and some EQ, just so the phonograph needle wouldn’t skip and certain sonic peaks wouldn’t mess with the needle,” says Was.

“In doing that, he altered the sound and that’s the sound everybody knows and loves.”

When it came to updating Van Gelder’s work for today’s format, Was says the label was placed in “a moral and ethical quandary.”

“Who are we to editorialize on this stuff, 50 years after the fact?” said Was. “What is the standard by which you remaster to? And we decided that the original vinyl was the standard: that’s what everybody decided who was involved – (Blue Note co-founder) Alfred Lyon, the musicians we decided to put out into the world: that’s what people bought and that’s what people loved. So we tried as closely as we could to master with the goal of returning to the original sound of the first pressings.”

Double GRAMMY winner Bernie Grundman (Album of the Year for OutKast’s 2003 gem Speakerboxxx/The Love Below and 2007’s Herbie Hancock’s star-studded tribute to Joni Mitchell, River: The Joni Letters), tasked with remastering the majority of Blue Note titles, confirms that vinyl sets up its own challenges.

“Vinyl doesn’t sound like the lacquer that goes to the factory,” he notes. “The medium itself changes it, and the processes it goes through when you’re making the vinyl actually changes the sound. It’s not the same as making a tape copy because that’s a re-recording process. With the vinyl, it’s not re-recorded, but it is transferred to metal through electroplating, and that actually affects the sound. So a vinyl disc does not sound like the tape or the lacquer. Once it comes back from the factory, you can tell the difference: It is warmer and it tends to take on a ‘bassier’ sound.”

Bernie Grundman

For the Blue Note project, Grundman built his own console.

“It’s a simplified, more straightforward board, with the functions we needed to simulate a lot of the things they did on the Blue Note albums.” says Grundman, who started his Bernie Grundman Mastering business in Hollywood and has since expanded to Tokyo. “So it bypasses completely our normal chain and toes right from the tape machine through very simplified electronics right to the computer.”

Oh, and Grundman, who is making Blue Note archived copies rated at 96/24 and 192/24, also built – or, in his terms, “hot-rodded” – the computer.

“It may be the cleanest-sounding computer in the industry, “ declares Grundman, who estimates he’s worked on over 70 Blue Note 75th Anniversary titles. “I don’t know if anything could match it, because I don’t think anyone has ever gone inside a computer and done some of the things we did.”

Virtually all remastering gurus agreed that when it comes to adjusting their approach for today’s formats, most don’t.

However, Bob Ludwig contends that digital remastering for iTunes is a slightly different beast.

“It’s not an equalization or compression thing, “Ludwig explains. “It’s a process of lowering the level into the encoder for the AAC file, and by lowering the level into the encoder, Apple has showed us that it creates much less distortion and can make a much more accurate encode to the point where a well made mastered-for-iTunes file sounds closer to the 24-bit master, than the 16-bit compact disc does.“

Mastering engineers spend a lot of time sifting through source material, sometimes contending with lost masters, studying copious notes made at the time of the recording, but in the end, if the job is done right, it’s worth it.

Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page says that when you get remastering right, it unlocks a door to the past and provides historical perspective.

“When you’ve got a chance to really listen to all of it, it gives a window — it’s like a portal — into that time capsule of when each album was recorded, “ he says. “And that gives you a really good taste. It works all the way right through the catalog.”

Blue Note’s Don Was says his exercise is one of passing it forward, to hopefully garner the music an introduction to some younger fans.

“At age 62, I find the music still means a lot to me.,” says Don Was. “This is what I listen to, to recharge myself, to feel good. I read this interview with Bob Dylan where he said that the job of the artist is not to tell you how they feel, but to put you in touch with your own feelings. And that line really stuck with me, because that’s what the Blue Note music does to me.

“I hope that in doing the reissues in this way, that there are some new fans of the music who will be able to enjoy the same experience and carry this music with them for another 50 years.”

Be the first to comment on "Remastering: The Art of the Sonic Facelift"