GRAMMY.COM

Game Music Video

October 16, 2013

Nick Krewen

GRAMMY.COM

Game on.

With 2013’s fourth-quarter rollout of XBOX One and Playstation 4, the release of over 300 titles for a variety of platforms, including consoles, mobile and online play, and the record-setting pace of Rockstar Games’ Grand Theft Auto V breaking the $1 billion sales barrier in just 72 hours, the current $66 billion global video-game industry shows no signs of disappearing anytime soon.

In fact, such trusted sources as DFC Intelligence and Forbes are forecasting video-game markets to substantially increase to $78 billion and $82 billion by 2017, leaving one to argue that music’s role in contributing to the bottom line of this visual medium is extremely vital, whether it’s been through soundtracks that have been assembled via song placements for titles like EA Sports’ perennially popular Madden or FIFA franchises, or scores delivered by respected composers like Martin O’Donnell for Bungie’s Halo and Russell Brower for Blizzard’s World of Warcraft and Diablo.

Jordan Mechner

“Music is a lot of things to gaming,” explains Jordan Mechner, the legendary game designer responsible for creating Karateka – which was recently modernized — and the successful Prince Of Persia video game franchise.

“It’s absolutely critical, and often unjustly overlooked in favor of graphics, because people tend to talk about graphics first, sound second, but they’re both equal partners and critical parts of the players’ experience.”

Mechner says there are several hallmarks of good game music.

“As a player, the music is often the key part of the atmosphere,” he notes. “It can set a mood, and if it’s well done, eventually becomes inseparable from our memories of the game.

“From a game design point of view, music can also be a cue to the player, warning them that something’s about to happen, or subtly clue them as to whether they’re on the right or wrong track.

“And of course, music in games does all the things that music does in film: it reinforces the action; creates a feeling of tension and tells the story as well. Game music can have a kind of light motif approach where music represents particular characters and themes, so the story is actually being told through music.”

With USA Today reporting a 178 percent growth spurt in the composer and music director professions over the past decade, and the U.S. Bureau Of Labor and Statistics projecting a minimum of “32,000 new music or composer job openings due to growth and replacement needs will need to be filled over the next decade,” opportunities for video game music scorers are looking so rosy that even Sir Paul McCartney is trying his hand at scoring some of Bungie’s Destiny.

However, breaking into this lucrative field is easier said than done, and usually requires a mix of luck and fortuitous timing to accompany a composer’s dazzling skill set.

“I went to my five-year college reunion and ran into my old roommate,” recalls Christopher Tin, who won the first video-game related GRAMMY Award in 2010 for Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying Vocalist(s) for “Baba Yetu,” a song he composed for the 2k Games and Aspyr partnership Civilization IV.

“He told me he had become a very prominent video game designer and asked me if I wanted to work on the game he was developing, which turned out to be Civilization IV. That’s the game I wrote ‘Baba Yetu’ for.”

Christopher Tin with someone not in the video game scoring industry

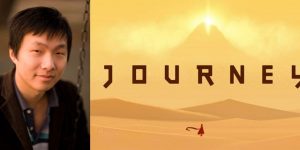

For Austin Wintory, who received a precedent-setting Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media nomination last year for Thatgamecompany’s Journey, it was meeting and working with game designer Jenova Chen at the University Of Southern California.

Jenova Chen

“We were doing student games much likes student filmmakers, and one of those – flOw — ended up being one that exploded and set all the wheels in motion. Sony was just getting ready to launch Playstation 3 and were looking for ways to be different from Microsoft, their chief competitor, and asked us to remake flOw as a Playstation 3 game.”

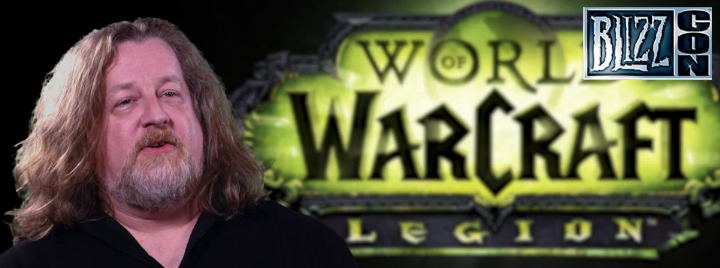

Russell Brower, senior audio director at Blizzard who presides over a department of 42 employees, including three staff composers, says he just keeps his ears open.

“There was a composer (Edo Guidotti) on (World Of Warcraft’s) Mists Of Pandaria whose work I heard in an IMAX film while I was on vacation,” he remembers. “The film was great, but I walked out of there going, ‘Who did this music?’ I found out and two years later, he was working on Mists Of Pandaria with us. That’s the best way.”

Russell Brower

Brower, a three-time Emmy Award winning sound designer who also keeps his hand in scoring, says he has a particular goal in mind when recruiting musical freelancers.

“It’s a very competitive market but what it really comes down to, is, can you tell a story with music?”

Prince of Persia’s Mechner says he starts his process by making a project wish list.

“We look at films and games we’ve admired, as a lot of composers now work in film, TV and game,” he explains. “We look at the demands of the project and try to find someone not only whose sensibility and style are privy to the project, but who also has the experience that’s needed for what we’re trying to do.

“For some projects, a composer whose experience is predominantly in film and linear media might be fine. For another project, we might need a composer like Christopher who has a deeper understanding of how music works in games and be able to create music that can be taken apart and recombined on the fly according to algorithms, something that traditional composers don’t have to deal with if they’re composing a single piece.”

Once the gig is secured, the role and scope of the music is determined by the project. If it’s a video game where the music is crucial as a storyline catalyst, usually the composer is brought in early, unlike film, where the music is often started and completed after the film has been locked.

“Scoring a film, you’re obviously working with a director, producer and the creative talent involved and you’re able to see the film when you’re scoring it,” notes Tin, who composes mainly from his home studio. “At times, when you’re working on a game, you don’t have much more than an Excel spreadsheet to tell you what you need to write. Basically, it’s almost like you’re relying on the audio lead and the in-house people to be your eyes and tell you what you need to do.

“When I score a game with an interactive score, I’m not the person plugging it into the audio engine and programming it. So I rely very heavily on the audio lead, usually from a staff member of the game developer. They sort of take my hand and walk me through what it is they need for the game and how it needs to work. In a lot of cases, I’ve basically put my trust in them, and I execute, musically, their technical needs.”

Another chief difference between film and game is the time factor, as video games often have more complex scoring demands, seeming as though they offer an infinite soundtrack.

“The solution that we’ve employed for decades is that we take a piece of music and make it loop eternally,” says Wintory, who took three years to write the music for Journey. “You can play Tetris for hours, and there’s 10 minutes of music that you hear tens of thousands of times. That’s a very clunky system, but it was a necessary step in the development of interactive audio.

“To be honest, I don’t know how much music I wrote for Journey. I’ll write a piece of music that could last 45 seconds, but it could also last three minutes depending on how it unfolds, because it’s not linear, traditional music. It’s written in a non-linear way, which is difficult for your brain to wrap around.”

Tin agrees.

“Everything that you write has to be modular, and it’s so piecemeal. It’s akin to actors acting in front of a green screen. That’s personally where the big challenge is for me. It’s like trying to paint a painting on jigsaw puzzle tiles, assembling the tiles later on and then hoping that what you’ve painted bears some resemblance to what you had in your mind when you started it.”

It’s also a medium where deadlines are tight, but loose enough for Russell Brower’s in-house Blizzard team to provide opportune feedback.

“I look at schedules and deadlines as a very constructive way to say, ‘hey, let’s set down our pencils for a few minutes, and look at each other’s work, or listen to each other’s work, and share it around the company,’” Brower explains. “We all spend some time every day, playing the games. And we’ll get comments about the music from character artists on the Diablo team, for a random instance. One of our maxims here at Blizzard is, “Every voice matters,” and we do listen.”

As far as the future of video game scoring is concerned, projects like Journey and Karateka that place music in the driver’s seat are opening a whole new world of interactivity.

“The music I composed for the recent update of Karateka was actually rhythm-based combat mechanic, so you had to listen to the music for cues on how to fight your enemy, and musically, it would give you hints and you’d have to tap in rhythms,” says Christopher Tin.

“I think that level of interactivity is not found on that wide of a scale, but I think we’re heading that way. There should be exciting developments in the way that music and sound can be implemented as audio engines get more sophisticated.”

GRAMMY.COM

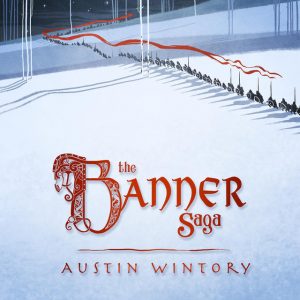

Sidebar: Behind The Scenes of The Banner Saga

Austin Wintory’s Play-By-Play Rundown

Released February 25, 2013, The Banner Saga is a Viking-themed tactical video game developed by Stoic after raising Kickstarter funding of almost $725,000. GRAMMY-nominated composer Austin Wintory spent 18 months on the project and breaks down his involvement with the score.

Released February 25, 2013, The Banner Saga is a Viking-themed tactical video game developed by Stoic after raising Kickstarter funding of almost $725,000. GRAMMY-nominated composer Austin Wintory spent 18 months on the project and breaks down his involvement with the score.

The beginning:

“I was brought in essentially from day one, which meant we were having conversations over how it should feel and play long before anyone even saw it. It’s a Viking mythology-inspired, turn-based strategy game with hand-drawn animation in an Eyvind Earle Sleeping Beauty style from the ‘60s. It’s exceptionally beautiful.”

The process:

“I’m writing music, in some cases, inspired by an e-mail description of what that part of the game is going to be like, before they’ve even designed the most fundamental architecture. Because I write the music first, they end up designing the game around the music. It’s not really step-by-step: I write music and then we put it in the game and we see if it’s working. The game is very rudimentary: missing graphics bugs, and you click on something that makes the game crash and you have to reboot your computer. It’s a work in progress.”

The lock-in:

“With The Banner Saga, at some point you have to start committing to recording, and this being an orchestral score, I recorded The Dallas Winds — this big ensemble of winds, brass and percussion — in a Dallas concert hall. Later I added Lisbeth Scott on vocal and a solo violinist from Detroit named Taylor Davis. Usually I record at the last possible second, so if I want to keep revising the music, I can. Once it’s recorded, you can’t change it. “

The finish line:

“The developers of the game have heard everything that I’ve written. I make MIDI mock-ups on my computer that sound approximately like the final music, and we code them into the game. By the time I reach the finish line — when I have these finished, produced, fully-recorded, mixed and mastered recordings –we’re essentially switching them out with the original placeholder mock-ups.

“Once that’s done, we do our final mixing and then you spend another few months ensuring that it’s working how you want it to in the game. You really are just fine-tuning – making things a little louder or softer, play testing, and having strangers come and play the game. If problems arise, I can solve them by adding a little music here, or make it stop sooner, to clear the way for X, Y, Z. You feel it out as you go.”

— Nick Krewen

Be the first to comment on "Keeping Score: The Rapidly Expanding Video Game Music Industry"