Nick Krewen

Special to the Star

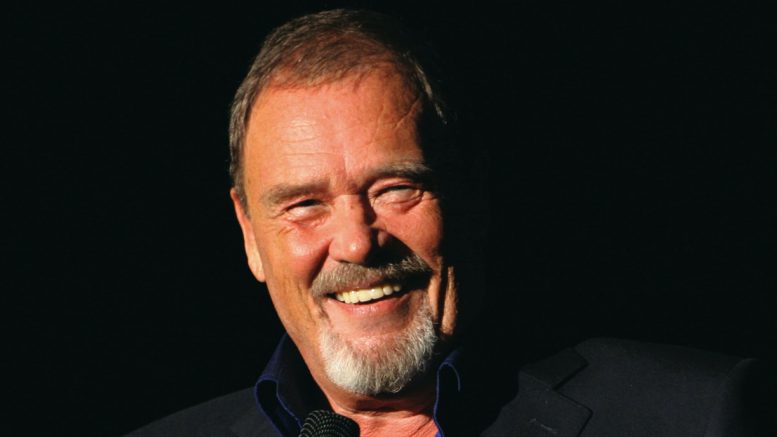

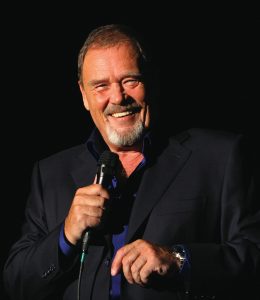

At 78, Blood, Sweat & Tears’ most recognizable voice – Toronto resident David Clayton-Thomas – is still fighting for justice on his acclaimed new solo album, Say Somethin’.

“Burwash,” the opening salvo of the two-time Grammy winner and Canadian Music Hall Of Fame member’s latest effort, describes his lengthy incarceration at Burwash Correctional Centre in Killarney, Ontario when he was 16 for what he calls “obstruction of justice.”

“I was run through the system like a side of meat/in some judicial abattoir,” Clayton-Thomas speaks against a bluesy acoustic guitar riff. “I was sentenced/ I was shackled, hands and feet/ 44 months behind bars.”

“Burwash” is bookended by “The System,” a reflective five-minute ballad where Clayton-Thomas soulfully laments with his unblemished-by-time tenor: “The system is relentless/the cycle never ends/It’s the same kids getting arrested/over and over again.”

It’s this experience that has prompted Clayton-Thomas to rally behind Peacebuilders Canada, a Toronto non-profit founded in 2002.

“It’s a wonderful organization,” Clayton-Thomas explains. “It’s involved in what they call restorative justice, which is intervening with 15-to-18-year-old kids who have come into the juvenile justice system.

“Before they end up in a reformatory, where the recidivism rate is just horrendous, Peacebuilders intervenes and diverts these kids from the courts into counselling. And where the justice system has an 80% failure rate – 80% of kids that go into prisons and reformatories will reoffend and spend most of their life in and out of the system – Peacebuilders has an almost 90% success rate.

“So, I’ve been very deeply involved with them for several years.”

The troubled years

Clayton-Thomas said in the late ‘50s, he ran afoul of a system wasn’t equipped to deal with someone like him.

“My major crime was that I was a homeless street kid,” he recollects. “And I was homeless because I was pretty badly abused at home. By the time I was 14 or 15, it became preferable to sleep in parked cars and abandoned buildings, then to go home and get the shit beat out of me, frankly.

“And back in the ‘50s, what did we do with kids we didn’t know what to do with? Put them into a reformatory. Thankfully, the system has changed, thanks to organizations like Peacebuilders.”

If most of the 10 songs on Say Somethin’ have a recurring theme, it’s social injustice: “Dear Mr. Obama” salutes the dignity displayed by the previous inhabitants of the Oval Office; “The Circus is a commentary on the current U.S. political situation and “Never Again” bemoans the endless gun violence south of the border.

“It’s an absolute epidemic,” notes Clayton-Thomas. “We talk about the pandemic going on right now, but at the end of the day, the epidemic of gun violence has killed a whole lot more people than Coronavirus. We’ve just grown numb.

“Once a week or so, somebody goes nuts and shoots up a shopping mall and we move on – it’s just another news story. As a Canadian, I find that horrifying.”

Dylan influence and English upbringing

Dating back to his 1965 anti-Vietnam War hit “Brain Washed,” Clayton-Thomas hasn’t stopped tackling the controversial in his music.

“(Bob) Dylan was a huge influence on me and I came out of that whole ‘60s movement where music – Woodstock – basically stopped a war,” he explains. “It changed an entire generation. I still hope that it has that power to speak for a generation, because a lot of people out there can’t speak anymore.

“The truth is getting harder to find every day, isn’t it? Maybe if you put it in music, there’s some truth in there.”

Born David Thomsett in Surrey, England, Clayton-Thomas was given his first break in the early ‘60s by Ronnie Hawkins.

“We had a ton of bars on Yonge Street. In the afternoons they’d have matinees with no alcohol, so under-aged kids could get in,” Clayton-Thomas recalls. “I joined a group of young kids who would go down to the Le Coq D’or every Saturday afternoon, sit in front of The Hawks and watch our idols – Robbie (Robertson), Garth (Hudson) and Levon (Helm).

“I just kept bugging Ronnie Hawkins until he let me get up and sing a song with the band. And that was it – he gave me a job, for a while. Then I ended up in The Shays. It’s just been one band to another ever since.”

With the Shays and the Bossmen, Clayton-Thomas enjoyed four Canadian hits on Roman Records – “Boom Boom” in 1964 (which led them to perform on NBC’s Hullabaloo, hosted by Paul Anka), “Walk That Walk” and “Brainwashed” in ’65 – and “Take Me Back” in ’66.

John Lee Hooker and the Cadillac break

But it wasn’t until a year later, while backing bluesman John Lee Hooker in Yorkville, that Clayton-Thomas began the journey that would lead him to front Blood, Sweat & Tears, the Grammy-winning, nine-piece jazz-rock ensemble known for hits “Spinning Wheel,” “Lucretia Mac Evil” and “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy.”

“I was doing coffeehouse gigs up in Yorkville and my earliest influences were John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed, Lightnin’ Sam Hopkins, Lonnie Johnson and people like that,” Clayton-Thomas recalls. “I’d take my acoustic guitar over between sets and play behind John. I knew all his songs and he just liked the way I played.

“I found out that he was going to New York. I said, ‘I’d love to play with you,’ and he said, ‘I’m playing at the Café Au Go Go in Greenwich Village. Drive my car down to New York and you’ve got a gig.’”

After Clayton-Thomas dropped off the Cadillac with the blues singer’s lawyer, he trekked to the venue and made a startling discovery.

“John Lee Hooker had cancelled: he had been booked on a big overseas America blues festival tour. So, there I was in Greenwich Village – $40 in my pocket, a guitar and no gig.”

The club’s owner was equally distraught…and after a few minutes commiserating, asked Clayton-Thomas if he had a band and if he’d like to fill the vacancy.

“I went out on the streets that afternoon looking for a band and I found a few guys because it was a hotbed of musicians. We opened at the Café Au Go Go that night and ended up staying there for almost a month, which is where I met the founding members of Blood, Sweat & Tears.” (The band had been founded in 1967 with keyboardist Al Kooper as lead singer.)

Collins, Colomby and chemistry

One of his sets was caught by folk singer Judy Collins, who brought along Blood, Sweat & Tears drummer Bobby Colomby.

The lack of a visa forced Clayton-Thomas to return to Toronto, but he didn’t stay long.

“A week later I got a call from Bobby saying, “Here’s the situation: (original bandleader and singer) Al Kooper’s gone; half the band is gone. We have four guys left, but we have a recording contract. Do you want to come back?’

“I was on the plane within an hour. We rehearsed the next day and Blood, Sweat & Tears was born, right then and there.”

The chemistry was instantaneous, with the nine-piece brass-and-reed combo selling over 10 million copies of its 1968 self-titled album – awarded Grammy Album of the Year – largely on the back of the Clayton-Thomas composition “Spinning Wheel.”

“’Spinning Wheel’ was actually written here in Canada,” Clayton-Thomas notes. “We had just had a No.1 hit with ‘Brain Washed’ and a small record company gave me a budget of $500 to cut a song. I had just written ‘Spinning Wheel,’ so I recorded a version and they were horrified. They wanted another ‘Brain Washed’ and basically rejected it.

“I stuck the song back in my guitar case and carried it around for two years until I started rehearsing with Blood, Sweat & Tears. One day I pulled the song out, played a few bars to (alto saxophonist) Fred Lipsius and he jumped all over it – he had the chart ready in the matter of hours. We played it that night.”

One of the band’s other huge hits, “Lucretia Mac Evil,” also had Ontario roots.

“‘Lucretia Mac Evil’ was about the bar girls that we met on the Ronnie Hawkins circuit all around Ontario,” Clayton-Thomas remembers. “There was a Lucretia Mac Evil in every bar. “

Five fruitful but exhausting years

Clayton-Thomas’ time with the group lasted five years, and he experienced milestones ranging from Woodstock to becoming the first U.S. jazz-rock band to play behind the Iron Curtain.

But playing 300 nights a year took its toll on Clayton-Thomas, and he left the band in January ’72, replaced by Jerry Fisher.

“Other than myself and Bobby, the rest of the band made their living by being on the road,” he explains. “So, whenever there was a vote for more touring, it was seven-to-two. They wanted to make all the money they could out of this while we were hot. Of course, the management, the agents, the promoters and everyone else were all in on it.

“We were a big money-making machine – and it was killing me. I just needed a break, so I imposed it. I had a lovely home in California – bought a place out there – and I just decided to quit. I took two years off the road.

“And then I discovered – and they discovered – that Blood, Sweat & Tears wasn’t worth much without me – and I wasn’t worth much without them. We put it back together again and went on for another 30 years (from 1974 to 2004).”

Canadian pride

Today, Clayton-Thomas lives on the Toronto waterfront and plays about 18 dates a year with a 10-piece band, although COVID-19 has scuttled his plans to perform here until further notice.

He loves being in Canada, addressing his love for the nation on “God’s Country,” the final track of Say Somethin’.

“I’m very, very proud of being Canadian,” he says. “Even though I lived in New York for close to 40 years, I never gave up my passport knowing I would come home to Toronto someday.

“I wanted to end the album on a positive note – and the most positive thing I can say is how much I love this country.”