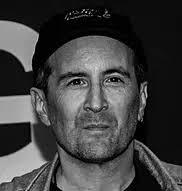

Max Hutchinson one of 300 pros still in there pitching tunes to artists

By Nick Krewen

Special To The Star

Wednesday, April 21, 1999

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — Max Hutchinson may not be Roger Clemens, but he knows how to pitch.

As one of Nashville’s 300 song pluggers, the middlemen who lob songs to recording artists for prospective album and single cuts, the Vancouver-born Canadian is starter, reliever and closer wrapped into one.

Unlike pro baseball, however, where pitchers proudly notch strikes as they help shut down the opposing team, Hutchinson guns for the hits.

His highly competitive field of dreams is country music, where Hutchinson is constantly angling for a World Series payoff — a hit single.

Today it’s Martina McBride. Tomorrow it could be Garth Brooks or Faith Hill. Hutchinson, who currently works for Not Stock/EMI Publishing, a joint publishing venture between EMI Music and noted session drummer Clyde Brooks, spends his 9-5 five-day workweeks representing a stable of six writers, making appointments, and filling a crucial link in Nashville’s musical food chain.

“Song pluggers are incredibly important,” says Renee Bell, vice-president of A&R for RCA Nashville, who often spends eight hours a day screening potential songs for a roster that includes McBride, Clint Black, Lorrie Morgan, Sara Evans, Mindy McCready and Andy Griggs.

“All of our music either comes directly from the writers, the publishers or pluggers.”

Bell relies on pluggers to eliminate much of the legwork.

“It’s important that they’ve done their homework, that they have an extensive knowledge of their catalogue, and that they’re familiar with the work of the artists they’re pitching. If they listen to the albums of the artists, they can get an idea of what appeals to them as melodies.”

It’s a hard grind in this cut-throat world, where artists will listen to as many as 3,000 songs a year preparing for a new 10 or 12 song album.

Multiply that by the number of other pluggers in the business, and Hutchinson admits he pitches no-hitters more often than not.

But when he belts one out of the park…

“It’s a lottery,” says Hutchinson, who has been plugging for five years. “You just have to keep showing up. Occasionally you get one.”

David Kersh is one person who owes his career break to Max Hutchinson’s persistence.

The babyfaced singer from Humble, Texas was an unknown until Hutchinson pitched him “Goodnight Sweetheart.” The song landed him his first Top Ten hit in the Fall of 1996, and spent a record 28 weeks in airplay.

At the time, Hutchinson was working for Kim Williams, a frequent contributor to Garth Brooks albums, and estimates he earned a $300,000 U.S. three-way split for Williams and co-writers L. David Lewis and Randy Boudreaux.

Boudreaux is especially appreciative.

“Every time I see him, Randy thanks me and offers to buy me a drink,” laughs Hutchinson, son of former W5 and Canada A.M. fixture Helen Hutchinson and her ex-husband Jack , a producer with Front Page Challenge.

Last year, Hutchinson mined gold Down Under with Australia’s biggest country hit of 1998, Gina Jeffreys‘ “Dancing With Elvis.” Currently, he has Randy Travis‘ hit single “Stranger In My Mirror” to add to his resume.

“I love my life,” says Hutchinson, 38, an affable fellow whose work wardrobe consists of a leather jacket, a t-shirt and shorts.

A former punk band drummer, MIDI programmer and A&R Manager at A&M Canada from 1984-1990, Hutchinson says he fell into song plugging by accident.

He moved from Toronto to Nashville eight years ago after joining Balmur Inc., Anne Murray‘s management company, to help establish a publishing division in Nashville.

A chance meeting with Kim Williams at a SOCAN workshop near Vancouver resulted in a job offering. Hutchinson jumped at the opportunity.

“I’ve always been a song guy.”

Song plugging may be unique to Nashville circles, but it was once the norm in New York and Los Angeles circles during the Tin Pan Alley heydays of the ’60s and ’70s. As The Beatles and other self-generating creators became more popular, they replaced the majority of pop artists looking for outside material. Nashville, aside from a plugging revival that’s underway in Los Angeles film circles due to the increased popularity of the soundtrack, has remained a holdout.

“Nashville’s whole motto has been `It all begins with a song,'” notes esteemed author and critic Robert K. Oerrman.

“The competition for great songs is very steep, so the conduit is the plugger. God bless them, they have to take ‘no’ all day long. It’s not a job I would like.”

Hutchinson admits there’s an art to his vocation.

“With song pitching, you have to be part salesman and part psychologist.

“It’s your instinct — whether you think it’s right for the artist, and whether you can sneak it by the personality you’re playing it for. A lot of it is getting past the watchdogs, who may have radically different tastes than the artist.”

On this sunny Nashville morning, Hutchinson has booked an appointment with Martina McBride’s watchdog, RCA’s Renee Bell. She’s gathering songs for a new McBride album due to begin recording in two weeks.

After a quick handshake, Hutchinson spends the next 20 minutes playing Bell a handful of Not Stock/EMI Publishing songs.

Bell leans back into her chair and turns to the window, staring into space as she listens to each song’s melodic structure and lyrics. After a minute-and-a-half of listening to “Come Find Me,” a piano-laced ballad, Bell dismisses it.

“I think we’ve reached our cap on ballads,” she says. “Mind you, if there’s a career-making ballad on there, I’m willing to listen.”

Hutchinson hands her another disc.

“This one’s called ‘Letting You Go With Love,'” says Hutchinson. “It deals with loss, and I understand, through the grapevine, that Martina recently suffered a loss of some kind.”

Bell smiles but doesn’t comment. She listens intently to the song, penned by Not Stock staffer Dinah Brein, and asks for a copy of the song with a lyric sheet.

Of the five songs, Bell requests copies of three including a mid-tempo love song called “I’m Ready To Fall” written by Canada’s Patricia Conroy.

“That was a good meeting,” says Hutchinson as he leaves RCA Nashville’s newly refurbished office in downtown Music Row.

“Last week I pitched Carole Ann Mobley, RCA’s director of A&R, the same five songs, and she didn’t take any of them.”

But even Bell’s willingness to accept copies of the songs constitutes no promises. She’ll listen to them further, and if she still likes them, they’ll be played for Martina McBride. McBride then has two options: either pass on the song entirely, or put it on hold.

The “hold,” a reservation of exclusivity for an artist so they can consider it for a future recording project, can be a nightmare for songwriters. Country artists impose holds without paying any compensation to the writers, and often take a minimum of six months to make up their minds.

Even when a song is cut, there are no guarantees.

“We pretty much know it’s going to be on the album when we see it,” says Hutchinson.

“It’s a job where there’s a lot of delayed gratification,” says Oermann.

“A song that was pitched successfully a year and a half ago gets a BMI Award in October two years later. In the meantime, you’re on to something else.”

Still, it’s a job that Hutchinson doesn’t think he’s going to tire of anytime soon.

The hours are easy, and it’s an occupation that involves a lot of social interaction.

“It’s like high school with money,” jokes Hutchinson. “Relationships are crucial.

“It’s also a job where I’m learning constantly, because what worked today is not necessarily going to work tomorrow.

“It’s like spiritual enlightenment. There’s no one true path.”