Vezt lets investors and fans purchase a share of future revenues from ‘Jodeci (Freestyle)’ and many more to come.

Only this time, it’s a different kind of money, one that could have far-reaching implications as the music industry pushes further into the realms of cryptocurrency, the speculative digital money that is secured through cryptography and recorded by blockchain technology.

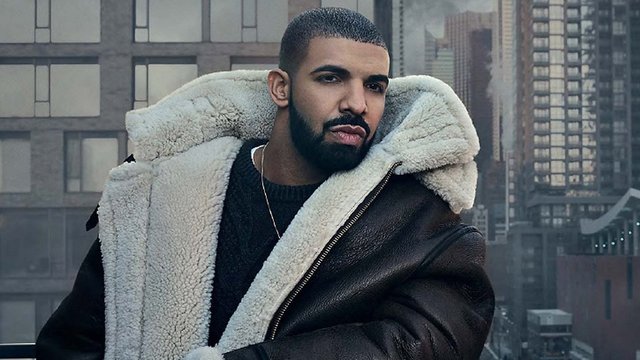

In a pilot project of sorts, and in the hope of creating a direct and transparent marketplace for creators and rights holders, Los Angeles-based blockchain outfit Vezt just completed its “ISO” — initial song offering — in late November: a chance for 100 non-U.S. residents to purchase up to 10 per cent of the copyright of a Drake song.

Steve Stewart, Vezt’s co-founding CEO and former manager of the Stone Temple Pilots, says it’s a win-win situation for both parties: the creator gets to dictate the terms of the transaction and generate immediate money, and the buyer winds up owning a piece of an artistic creation, which could have deep sentimental value to that person.

“We think that everybody who participates in the creation of music should be compensated and this is a direct way to monetize intellectual property for the creators,” says Stewart, who created Vezt just over a year ago with Robert Menendez.

To prove the viability of its business model, Vezt recently concluded its first “token generating event,” by offering “Jodeci (Freestyle),” a 2013 track recorded by Drake and J. Cole, as the musical guinea pig.

The event, which concluded Dec. 1, resulted in the purchase of over 2.8 million VZT tokens for a total of $1.38 million (U.S.). Combined with a previous private investor offering that raised another $3.2 million (U.S.), the result left Stewart ecstatic.

“If we had raised $100 and given up no equity, I’d be amazed,” says Stewart. “To do more than $4.5 million in a short period of time is almost inconceivable.

“The important thing is we now have enough runway to build and scale our platform in the most efficient and expeditious way.”

To be clear, the writer’s share of the song doesn’t solely belong to — and wasn’t offered by — the Toronto rap god himself, although Drizzy’s superstar name was definitely a selling point.

But one of its co-writers whom Stewart refused to identify — Dewayne Brandley, Simon Rufus William III and Roosevelt Harrell III, the producer known as Bink, are among those listed — cashed in, selling his 10 per cent share to Vezt.

Stewart says Vezt owns a fraction of the copyright shares of 27 additional songs recorded by the likes of Kanye West, John Legend, Rick Ross, Dr. Dre and others to help jump-start its platform, which it’s planning to open to artists and rights holders by summer 2018.

“Anybody who owns rights should be able to transact them,” Stewart explains. “That’s the basis for our platform.”

Vezt co-founders Robert Melendez (l) and Steve Stewart (R) with producer Andre “Dre” Lyon.

Photo By: Ken Alkazar

The premise is simple: creators and rights holders of intellectual property offer some share of their song rights to potential buyers on the Vezt platform.

These song shares are purchased via Vezt’s VZT utility tokens valued at approximately $0.35 (U.S.) each. In exchange, the creator forgoes those portions of the rights for a predetermined term — usually one, three or five years — during which the purchaser receives whatever pro-rated royalties and revenues are generated.

Song-rights details are automatically encoded on the Vezt blockchain and tracked by royalty-collecting performance rights organizations in 137 countries around the world, gathering income from various sources (see “How It Works” below). The rights revert to the creator at the conclusion of the term.

While public interest in cryptocurrency has spiked lately on the heels of Bitcoin’s rocketing value — from 8 cents in 2009 to more than $11,000 (U.S.) today — a few recording artists took notice earlier. British singer and songwriter Imogen Heap was the first, independently releasing a song in 2015 called “Tiny Human” that could be purchased with ETH, perhaps the second most popular cryptocurrency after Bitcoin.

The latest projects include Icelandic singer Björk, who has offered consumers the chance to purchase her just-released Utopia album via several digital monies. Slovenian electro-producer Gramatik, who is booked into the Danforth Music Hall in April, has gone one better: establishing his own GRMTK cryptocurrency, which he launched in Zurich in November.

Artist manager Steve Stewart says one of the reasons he launched Vezt is to resurrect the value of music, which he says disappeared with the arrival of file-sharing company Napster. By relying on a song’s music royalties, Stewart is convinced he can help turn around music’s — and music makers’ — recent misfortunes.

“After a song is pumped up and released, there’s a spike if it’s put out on the radio or toured behind for a period of time,” he says. “After that spike comes down and levels out, you pretty much have a level income stream going forward.

“That’s why people like (David) Pullman could do the Bowie Bonds 25 years ago: they securitize music royalties. We’re seeing firms like Goldman Sachs today look at music securitization options again because it almost acts like a bond . . . it’s fairly consistent as far as income goes.”

Pullman, creator of the “Bowie Bonds” that saw David Bowie receive $55 million (U.S.) tax free in exchange for the majority of his album and publishing catalogue being securitized for 20 years, says this type of transaction probably wouldn’t interest songwriters with extensive catalogues “because they’re too conservative,” but are more for creators who want “liquidity now.”

Stewart believes that once the Vezt platform is fully running, the majority of song-share purchasers won’t be from Wall Street.

“Honestly, we think that 80 per cent of our buyers are going to come from an emotional place: they’re going to buy it because it’s their favourite song,” Stewart says. “Every time they hear that song streamed, every time they hear it in a club, every time they hear it on the radio, they know that they’re making something along with the artist.

“We see a lot of our buyers coming at a relatively modest dollar value, anywhere from $1 to $100. So for the price of a T-shirt — $25 or $30 — they can buy a piece of a song that moves them emotionally.”

With many musicians struggling to fully devote time to their craft and others lamenting the terms of onerous recording contracts that wrest intellectual property control away, Stewart says Vezt has great potential to be a music industry game changer.

“Artist/creators get a publishing deal and it might cost them 25 per cent of their copyright,” says Stewart. “They get an admin deal, that might cost 5 per cent to 10 per cent. They get a label deal and a label might take 85 per cent. There’s a lot of people with their hands in pockets, as is with the music business traditionally.”

And his company won’t stop at music.

“We’re looking at anything that has an IP component to it,” says Stewart. “We’re looking at books, shows, film, TV, video content. . . . We’re looking to be the marketplace for IP all around the world.”

How it works

Once a song is written, 100 per cent of its copyright (which entitles the owner to money generated by streams, radio airplay, TV broadcasting or even a commercial spot) belongs to the writer or writers. Typically, the writer signs a publishing deal giving half of that to the publisher; if there is more than one writer, they each get a chunk of the writer half.

Under the Vezt plan, creators could sell the right to the cash generated over a given period in exchange for the buyer’s cash now. Once the transaction is complete, the funds are immediately credited in the creator’s account and the deal is recorded in the blockchain for posterity. Song-rights details are automatically encoded on the Vezt blockchain, too, guaranteeing the buyer proof of possession and opening the door to cheques from royalty-collecting performance rights organizations in 137 countries around the world.

The purchase of the rights is made using VZT tokens, which can themselves be bought with the more established cryptocurrency ETH or, for a service fee, with recognized currencies such as U.S. or Canadian dollars.

The rights revert to the creator at the conclusion of the term.

Be the first to comment on "Want to buy a piece of a Drake song? Track’s rights sold via pioneering digital currency scheme"