Nick Krewen

GRAMMY.COM

July 2005

Billy Gilman is back from recess.

Professionally derailed by the trials of puberty for the past three years, the Rhode Island country singing sensation is hoping for a new lease on life with his recently released album Everything And More.

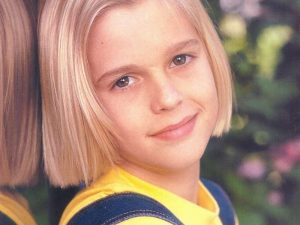

Billy Gilman during his “One Voice” days

But Gilman, who stormed onto the Billboard country charts at the age of 11 as the genre’s youngest recording artist with the double platinum album One Voice in 2000, finds a new challenge awaiting him at 17: the transition from child to adult music star.

“I loved having no worries as a kid. Now I have a lot of worries, ” he laughs. “Now I get nervous a lot more. Before, when I put out a record it was, like, ‘Oh, I’m excited. I’ve got nothing to lose.’

“Now I’ve had a career for six or seven years and the nerves and reality are coming into play. That little-child innocence isn’t there anymore.”

A very young Aaron Carter

Aaron Carter can relate. After selling over four million records of his cherubic pop, the 17-year-old younger brother of The Backstreet Boys’ Nick Carter also finds himself at an important crossroads. As he records his sixth album, he’s faced with the task of choosing a sound that will appeal to more mature audiences without alienating his established fan base.

“It’s really tough,” says Carter, who has a role in the upcoming 20th Century film Supercross. “Eventually your fans grow up and don’t want to listen to cheesy music anymore. Some of them lean towards more rap music, some of them lean towards more Ryan Cabrera-styled music — it’s really just about finding the middle, but also being comfortable.

“Right now, I’m just trying to find and figure out the style of music I really want to do, which is a little bit of R&B and a bit of soft rock. I want to stay along the lines of some of the stuff I’ve done, but also move on.”

The conversion to long-term artistic credibility isn’t insurmountable, but it is difficult. As Reebee Garofalo, Ed.D Clinical Psychology and Public Practice and Community and Media Technology professor at Harvard University observes, most young acts find their public introduction targeted at an equally youthful audience, with trained professionals controlling and manipulating the creative aspects of their vocations.

As performers develop, their tastes change.

“In the early stage of teen poppers’ careers, you’ve got the old school Tin Pan Alley division of labor with professional A&R people matching singers with professional songwriters to come up with material,” notes Garofalo, author of Rockin’ Out: Popular Music In The U.S.A.

Reebee Garofolo photo by Joe Mabel

“As they mature, their music becomes a more personal statement and that dictates a much different division of labor, with them taking on more of that creative function.”

Compounding matters is the young artist’s image, often sculpted to exploit their budding sexuality. If their image overshadows the music, Garofalo says the chances of post pin-up career survival are slim.

“If there’s no substance behind the image, when that image is no longer appropriate, they’re going to disappear.”

Image still plays a crucial role even if the music does have legs beyond a teen audience, finds Anastasia Goodstein, founder and publisher of Ypulse: Media For The Next Generation, a blog about Generation Y for media and marketing professionals.

“It’s really a question of how far you can go before you cross the line and alienate your audience,” notes Goodstein, also manager of Viewer Created Content at Current TV, the new Al Gore-financed television channel for 18-34 year olds launching August 1.

“If your audience is mostly young people, especially if it’s girls and tweens, then I think you walk a really fine line with how far you can go.

Anastasia Goodstein

“Someone like Hilary Duff or even Mandy Moore, when she was doing music, seemed to keep that in check. But for Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, going from somewhat innocent to full-on sexual adult outside of their performances, in their personal lives, in the tabloids and the gossip blogs, it does damage them a little bit. It alienates a lot of the people who may have been buying their actual music.”

Goodstein says young stars searching for a mature audience should find the right producer.

“If you can come back with something kind of good, as Justin Timberlake did — he broke out and took it to the next level, making very smart choices about his solo effort,” says Goodstein.

“Finding really good producers will help you make the transition.”

She also suggests that teen music idols avoid any behavior that would make good tabloid fodder.

“A lot of people would say any publicity is good publicity, but for some of these former teen stars, anything that has to do with being arrested, hitting somebody or partying a little too much and making an ass of yourself – I don’t think that stuff looks good or does anything but alienate their younger core audience.”

Then there’s always the danger, Goodstein warns, of falling into the trap of multi-hyphenated talent.

“It always seems like everybody wants to be that triple threat – do movies, TV and everything else,” Goodstein explains. “Very few people can successfully do it, and maybe the risk of that is doing it really poorly. So that temptation to spread yourself a little thin and try to be the triple threat and the star versus the music star might be a pitfall for some people.”

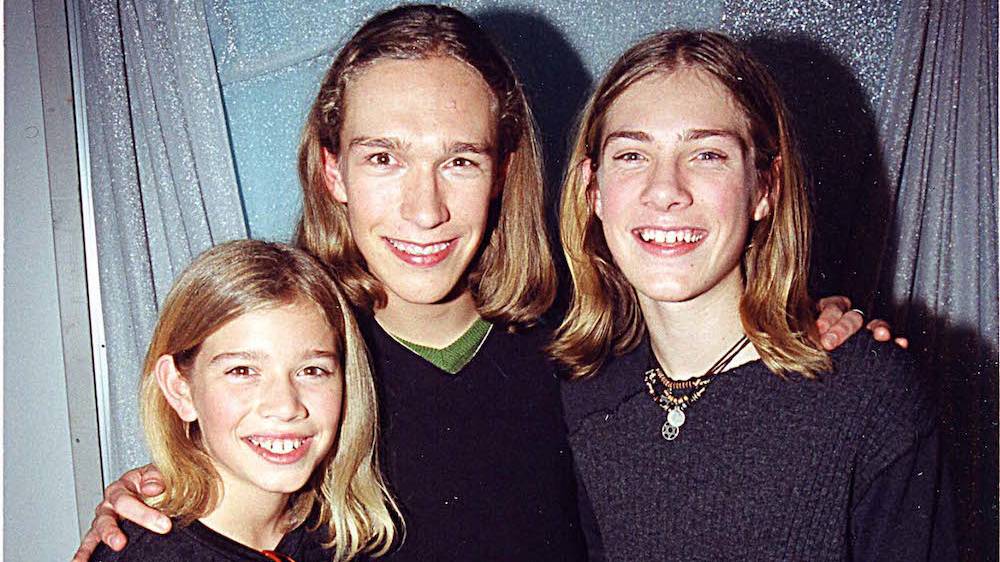

Self-contained artists – those who write, record and perform their own music – tend to weather the adjustment better, says Isaac Hanson, guitarist with the Tulsa sibling trio Hanson. When the band debuted in 1997, Isaac, Taylor and Zac — 16, 13 and 11 at the time — hit pay dirt with its debut album Middle Of Nowhere, selling more than four million copies.

Hanson then…

Hanson…now

Now running its own 3CG Records label, Isaac Hanson says the trio is currently in a rebuilding process, selling over 150,000 copies of its 2004 album Underneath, scoring a U.K. Top 10 hit with “Penny & Me” and continuing to sell out soft-seater venues wherever they tour.

“I don’t feel like the barriers are insurmountable because the foundation that we have musically is the only thing that ever mattered,” Hanson states. “We are in a better position than ever because we’re dealing with a growing fan base.”

Hanson says that for most adolescent recording artists, a backlash may inevitable considering the cyclical nature of pop music.

“When you reach a critical mass, that backlash happens. It’s always a challenge. Whether you’re U2, Maroon 5, Hanson or anybody else, it’s about continually moving forward. That’s difficult no matter who you are.”

Aaron Carter, whose older brother’s Backstreet Boys found themselves back near the top of the Billboard Top 200 charts recently after a four-year absence, remains undeterred.

“My ultimate goal is to just make my fans happy and sing good music for them, because eventually I’m not going to be that young, cute-looking kid,” he explains. “And I don’t want to be looked at like that anymore. I don’t want to be referred to as that and just being in the pop star magazines.

“The main thing is being careful and watching where you’re stepping, because eventually there are going to be some holes that you’re going to step in, and getting out is my problem.”

Billy Gilman is also optimistic. He feels that his time away from the spotlight will bolster interest in his current album.

“The advantage is that people are wondering what I’m sounding like, ” says Gilman. “There’s a lot of intrigue now.”

But he’s all too aware that public taste can change on a dime.

“You can’t see what tomorrow is going to bring,” notes Gilman. “Your stock can fade as quickly as you came, so you live each day in the moment.”

Be the first to comment on "The Career Commencement Challenge"