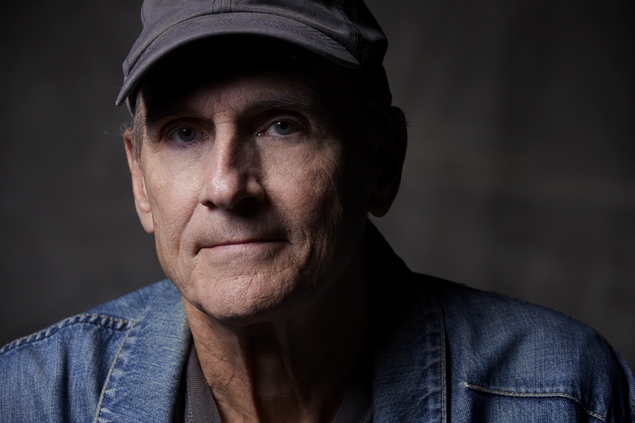

Nick Krewen

Special to The Star

Not only has he seen fire and rain: legendary singer and songwriter James Taylor has also seen more than his fair share of pain.

Despite selling more than 100 million albums in a 54-year career that has earned him worldwide adulation, five Grammy Awards, inductions into the Rock and Roll and Songwriters Halls of Fame, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and Kennedy Center Honors for his signature folk-pop sound and soothing tenor, Taylor suffered through opioid addictions that lasted from the mid-‘60s to 1983.

Although it’s been decades since he conquered his vices of heroin and methadone, Taylor – who releases his 19th album American Standard on February 28 and follows it up with an April 27 appearance at Scotiabank Arena with special guest Bonnie Raitt – says those in recovery have two sure-fire cures at their disposal.

“There’s only one real game in town and that is 12-Step programs of recovery,” Taylor said recently down the line from his Boston home. “Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous, Gamblers Anonymous: all of these 12-step programs are really the only thing that can be counted on to work at all.

“Whatever your problem is with 12-step programs, you’ve got to get over it, and somehow bring the body and perhaps the mind will follow.”

And the other remedy?

Surprisingly…not music.

“The thing that is so difficult about early recovery is how physically uncomfortable it is for people,” Taylor explains. “Just the drudgery, the constant discomfort just wearing on you, the inability to sleep and feeling like you can’t stand being in your own skin.

“For that, the answer is physical exercise. Physical exercise was absolutely essential to my recovery.”

Taylor, who turns 72 on March 12 and recently released an audio-only bio called Break Shot, says it wasn’t simply a case of going to the gym and working out an hour or two a day, but exerting himself to the point of exhaustion.

“I was an opioid addict – and what you get when you recover from opioids is the opposite of what they did for you when you were getting high,” he recalls. “You get all of that back – all of that discomfort, that agitation, the anxiety – the clock seems to slow down and creep by and every day is just a trial. All roads seem to lead you back to your substance of abuse.

“But if you can exhaust yourself physically – get to the gym, get on the bicycle, go out into the woods and walk until your exhausted, that’s what’s going to save you – physical exercise. That’s the only thing that saved me.”

As for music, that provided Taylor with the incentive to keep going.

“I think you have to have enough in your life that’s positive, brings you along, encourages you to move forward and that you don’t want to lose,” he states. “Music was that for me. It’s such a positive thing for me that I didn’t want to lose it. In that way, I think it not so much saved my life but gave it purpose.”

Although Taylor is best known for such original soft-pop classics as “Fire and Rain,” “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight” and “Shower the People,” he’s also done well with other people’s material, scoring big chart-toppers with covers of “You’ve Got A Friend,” “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)” and “Handy Man.”

Co-produced with master guitarist John Pizzarelli and engineer Dave O’ Donnell, Taylor’s new album, American Standard, follows a similar path: the 14 tracks offer his guitar-oriented takes on several American Songbook era classics, ranging from “God Bless The Child,” “It’s Only A Paper Moon” and “Pennies From Heaven.”

“They definitely speak to me and have timeless messages,” Taylor notes. “‘God Bless the Child’ or, from (the musical) South Pacific, ‘You Have to Be Carefully Taught,’ sort of a condemnation of racial hatred.

“This era of music – the great musicals of the ‘40s and ‘50s – and the sort of popular hits of the ‘20s and ‘30s – it’s the highest point, I think, of Western cultural popular song.

“Those songwriters were charged with making an emotional point in a musical or carrying the action to another place or furthering the plot. These guys were really song crafters: (Richard) Rodgers and (Oscar) Hammerstein; Frank Loesser, Cole Porter, The Gershwin brothers; Johnny Mercer, Yip Hardburg, Harold Arlen – they were as good as popular music got.”

These works were also seminal to Taylor’s musical upbringing in the Chapel Hill, North Carolina home he shared with his physician father, his mother and four siblings; three of whom – Alex, Kate and Livingston – would undertake their own journeys into professional music.

“These are songs that I’ve played on guitar for a long time,” he explains. “A lot of these songs were part of the family record collection and I’m very grateful that this music formed the foundation of my own musical life.”

Ever the student, Taylor said that preparing material for American Standard “sort of stretched me. It forced me to learn a different vocabulary.”

Taylor says the era also informed his originals.

“I’m sure without any doubt, a song of mine like ‘Mean Old Man’ or ‘Sweet Potato Pie’ or ‘If I Keep My Heart Out of Sight’ or ‘There We Are’ – these songs are very much inspired by this era of songwriting.”

Taylor also hasn’t abandoned his own craftsmanship, although his last album of original material, Before This World, was released in 2015.

“There are always seeds of new songs – and I put them down on a pocket recorder – actually, these days, mostly just on my phone,” he admits. “At a certain point, I will listen to all of those things and start taking them as song ideas, and I’ll go to work.

“But it means protecting the time – I have to sequester myself and steal away, because I tend to get distracted otherwise – and it really does require some concentration.”

Taylor describes his creativity as a channeling of sorts.

“A certain amount of a song is like a lightning strike – hopefully you get 25% of the song and a strong idea of what it’s going to be – and then you have to circle back and go to work on the thing,” he explains. “But even that is a voyage of discovery and it’s like going to sleep and going down to the well and drawing up water from deep below the Earth. What comes up in the bucket is always a surprise.

“It’s as if the real work is happening at a subconscious level and I just have to be quiet and patient enough and show up for the process so that I can allow it to happen. But that’s how it feels.

“I also tend to go back to the same themes over and over again – songs about my father, songs about my wife, songs about recovery, songs that are sort of spiritual songs for agnostics; songs for the environment sometimes. I have my themes that I continue to visit and revisit. I write songs about my audience and what it’s like to be in this life, you know?”

A liberal and environmental activist, Taylor says that “it’s important that we bring human activity in line with the health of the planet.”

“As we continue to overpopulate the planet, it can’t go on this way,” he warns. “So, we need to get to work; we need to cooperate globally. It’s a huge task and it could be a unifying principle – but the alternative is that we’ll start competing as nations for what’s left of the world’s resources, and that would be a pity to see it go that way, for the damage it’ll do to the Earth and for the wars that inevitably will follow.

“I think it’s going to take a catastrophe to wake people up. I’m just hoping that the catastrophe won’t be too catastrophic.”

About to embark on a 12-date Canadian tour in April and May, Taylor says he admires the country.

“There’s a sense of altruism that I feel in Canada,” Taylor declares. “I think that you’re doing an awful lot better at governing yourselves than we are these days and you probably see your own situation much more clearly than I do – and might want to dispute that – but things have come to an unbelievable path here. I feel as though we’re fighting the Civil War again.

“As a New Englander, I feel a kinship with the Québécois and the Maritimes, and I love Toronto as a melting pot – as a real example of a cosmopolitan and modern city that is so wide open and positive. Again, that may be naïve of me too, but that’s the sense I get. “