January 13, 2006

Major labels have put catalog mining into the hands of specialized divisions

GRAMMY.com

Nick Krewen

If you’re a Ray Charles fan, Christmas has come early.

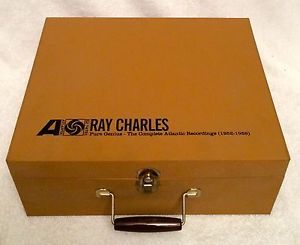

To celebrate what would have been his 75th birthday, Rhino Entertainment recently issued a pair of Ray Charles albums — a posthumous duets project called Genius & Friends and the more elaborate Pure Genius: The Complete Atlantic Recordings (1952-1959), an eight-disc set that includes a DVD of the multiple GRAMMY winner’s appearance at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival.

The latter collection includes a previously unreleased 1953 rehearsal session with Atlantic Records co-founder Ahmet Ertegun — a disc that almost didn’t make it onto the package.

“We were darn close to printing the booklet when we discovered some extra outtake material that ended up making it on the box,” says Kevin Gore, Rhino’s executive vice president, sales and marketing.

Unearthing last-minute treasures may be one of the few hazards of vault research, but it’s a dilemma most labels — especially those like Rhino, Sony BMG’s Legacy and Universal’s Chronicles that are specifically mandated to dig through their archives for materials that will enhance a reissued album, add value to a compilation or bolster a box set — are thrilled to have.

“It’s one of the good news/bad news situations that you encounter when doing vault research,” Gore explains. “You think you’re done with your job and you’ll turn up something at the last minute.”

For Ray Charles fans, the rehearsal sessions only add to the set’s allure.

Listed at a suggested retail price of $149.98, the project’s eight discs are housed in a ’50s-era portable record player case that opens to reveal a reproduction of Charles’ “Mess Around” 45-rpm single sitting on a turntable. The collection also includes an 80-page linen-bound hardcover featuring an essay written by David Ritz and vintage liner notes from respected critics Nat Hentoff, Leonard Feather and others.

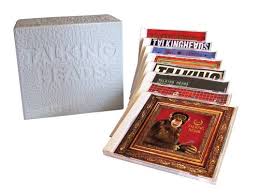

Pure Genius isn’t the only extravagant package Rhino is offering this fall: There’s the Talking Heads‘ Brick, a white plastic box with raised letters that contains their entire studio album catalog reissued in the DualDisc format, as well as One Kiss Can Lead To Another: Girl Group Sounds Lost & Found — a 107-artist girl group omnibus packed inside a hatbox.

“Packaging for Rhino has always been a very important component of how we present music to people,” Gore states. “It’s a big part of the marketing.”

Although Burbank-based Rhino has been assembling collections for 27 years — intensified by its sale to the Warner Music Group in 1998 and subsequent access to the company’s substantial archives — it hasn’t cornered the market on catalog exploitation.

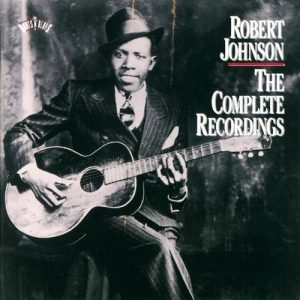

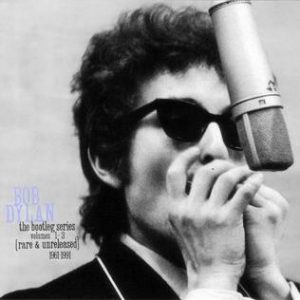

In 1990, Sony Music established the Legacy imprint to mine their vast 100-year-plus-old catalog, releasing such highly acclaimed compilations as Robert Johnson’s The Complete Recordings, the Bob Dylan Bootleg series of rarities and live recordings, and the ongoing all-encompassing Miles Davis sessions.

Sony Music’s merger earlier this year with BMG added more titles to Legacy’s impressive reservoir. “Obviously now we’ve got even greater depth,” notes Adam Block, Legacy’s general manager.

Not to be outdone, Universal Music Enterprises has not one, but two labels devoted to archival exploitation: Chronicles — and in a competitive nod to Rhino — Hip-O.

Determining which projects get the deluxe treatment is dependent on a number of factors, says Legacy’s Block, whose upcoming label projects include a five-disc CD/DVD rarities retrospective from Billy Joel called My Lives and a double-disc 30th anniversary edition of Patti Smith‘s Horses.

“To some degree, the decisions are made intuitively. In other instances, we are opportunists. There’s a constant and ongoing assessment of the entire catalog for their critical relevance, their commercial relevance or ideally both. At the end of the day, there is a business to this art. Ultimately, finding that balance between art and commerce figures into all of our decisions.”

Although each label rep declined to disclose what percentage their imprints contribute to the corporate bottom line, one can assume it’s substantial: Universal, Rhino and Legacy each release a minimum of 150 projects per year, with the numbers maxing out at closer to 300.

According to Block, loyal fans are the primary consumer targets; however, he notes his label is always on the lookout to expand an audience.

“Whether you’re talking about Frank Sinatra or AC/DC or Barry Manilow or RUN-DMC, we attempt to identify and reach the existing core first and then build it out from there,” he declares.

Box sets and greatest hits packages aren’t necessarily cheap to produce. Projects can take anywhere from six months to several years to research, clear and compile — and there’s always the unexpected prospect of a delay.

“There are a lot of things out there that you’d like to license that for various reasons can’t be done,” says Pat Lawrence, vice president of A&R for Universal Music Enterprises, whose label is prepping a DualDisc of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Gimme Back My Bullets that features a live BBC concert performance.

“Often it’s just a matter that it can’t be done now, so the rules may change again in two, three or five years.”

There’s also the challenge of turning a decent profit. “You put a lot of your costs into making the package hum,” Rhino’s Gore explains. “What we try to do is make a compelling package, have great notes, the right music in it and all of that adds up in many cases to not the greatest of margins.”

Wherever possible, the labels are also trying to keep the artists or their estate happy, though that’s not always possible.

“If we’re working with an artist, we’re deferring to that artist,” says Legacy’s Block. “That’s our policy. But an artist may not feel it’s the right time to do something or there are occasionally contractual issues that come up. However, we think that those relationships only legitimize what we’re doing.”

When it all finally comes together, Rhino’s Gore says it’s the fan base that will let them know if packages like Ray Charles’ Pure Genius live up to their expectations.

“We usually hear about it,” he says. “We have a pretty active Web site where people will tell us whether we’re doing a good or bad job.”

(Nick Krewen is a Toronto-based journalist who has written for The Toronto Star, TV Guide, Billboard, Country Music and was a consultant for the National Film Board’s music industry documentary Dream Machine.)

Be the first to comment on "Unlocking the Vaults"