Survival Of The Fittest

Nick Krewen

Grammy.com

July 2002

It’s one thing if you’re an established artist like Prince, who sold 40 million records during his Warner years and wants to forego the major label route in favor of his own Internet venture www.npgmusicclub.com.

It’s another, however, if you’re an artist that was perfectly happy to be nestled in the bosom of a major record company, only to have the carpet yanked from under you due to a corporate takeover, merger, restructuring, termination or some other measure beyond your control.

And if you’re just enjoying your first taste of success and banking on a long-term career, the sudden mid-stride cut-off can be devastating.

Santa Barbara, CA., pop rock outfit Dishwalla is feeling the pinch. In 1996, the A&M recording act seemed unstoppable, topping the charts with “Counting Blue Cars” and striking gold with its debut album Pet Your Friends. Two years later, the band was hoping to build further momentum with its sophomore effort And You Think You Know What Life’s About. Unfortunately for Dishwalla, Universal Music had bought A&M as part of its $10.4 billion takeover of PolyGram N.V. a year earlier and through corporate restructuring, effectively neutralized the label.

“The timing was bad,” Dishwalla singer J.R. Richards recalls. “Our second record came out right when A&M was sold and the label was purged. There weren’t very many staffers left and there certainly wasn’t much money to work the record. We paid ourselves to tour for a year, and continued to work the record any way we could.”

Dishwalla

Despite Dishwalla’s efforts, the album stiffed. Although the band wasn’t among the estimated 3000 employee and 200 artist Universal casualties — shifting to Interscope under the reorganization – it was a temporary reprieve. Then-president Tom Whalley confessed he had too much on his plate – ostensibly brought on by the takeover – and Dishwalla negotiated its release.

“We wasted a year sitting in limbo trying to figure out what we were going to do,” says Richards.

Singer and songwriter Poe found herself in a similar boat last November when AOL Time Warner-owned Atlantic Records set her adrift, despite a sunny forecast for Haunted, her sophomore album.

“To this day I’m not exactly sure how it all went down,” says Poe, a direct signing of Atlantic-distributed Modern Records who had achieved earlier gold sales of 500,000 copies for her 1995 album Hello.

“From my perspective, I was on the road looking at a record that was growing beautifully. We basically had a hit on the radio with “Hey Pretty.” The tour was going beautifully and all the right things were happening. I think AOL taking over Atlantic (Time Warner) was certainly no small thing in terms of my fate there.”

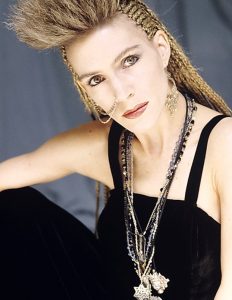

Poe

At a time where majors seem more interested in shoring up shareholders than singers, an unprecedented number of major label castoffs are fighting for survival and exploring new opportunities. The good news is that for many of them, there is indeed life after merger, but not without sacrifice.

For Dishwalla, the answer is the independent route: The band recently released its third album Opaline on L.A.-based Immergent Records.

Richards describes Dishwalla’s deal with Immergent as “a joint venture where we basically split everything 50-50,” but admits there are tradeoffs, especially the clout of having a bigger star on the label.

“They don’t necessarily have the leverage a large label would,” he explains. “When things started happening for you at A&M, I know they could walk into The Tonight Show and say, `Look, Sting’s got a new record coming out. We’ll give you the first shot of him playing live if you put Dishwalla on.’ Now we’ve got to pretty much prove things on our own. It’s definitely tough for a band like us.”

The group is touring, and Richards reports that Opaline sales for the first two months are in the vicinity of “50,000-60,000” copies.

Radio accessibility is another concern. Jane Child, a former Warner Bros. artist who scored a 1990 gold hit “Don’t Wanna Fall In Love,” is attempting to reintroduce herself through Sugarwave, her own indie (www.janechild.com). But her attempts to get her new album Surge on the radio have fallen on deaf ears, and Internet marketing is posing its own challenges.

“Unless you’re on one of the five majors and you’ve got the machinery behind you, it’s impossible to get yourself any kind of promotion,” sighs Child. “So you have your distribution and everything taken care of through the Internet — nobody knows who you are. And there’s no way of sending any smoke signals to the world to let them know because all the major media outlets are tied up by the big boys.”

Jane Child

And Poe, who is weighing her options, is concerned about tour support.

“For an artist like me, touring is essential,” she notes. “But I’m intrigued by what Moby has done with licensing, just in terms of the idea that there may be other ways to get your music out there. There are a lot of different ways to move forward, and whatever it is, it’s going to be a uniquely structured situation. Music can be distributed differently, thought of differently, financed differently and frankly I find that extremely exciting.”

While Poe is still exploring potential partners, another artist may have found financial support through a centuries-old idea: patronage.

Jane Siberry

Click onto www.sheeba.ca and you can sponsor blocks of Jane Siberry’s studio time for donations in $100 increments through her Patron Of The Arts Programme.

“It’s a tricky thing, because I don’t feel comfortable with charity, or people having strings attached, so I had to set it up in some way that people are going to get something special for it,” says Siberry, who has financed two albums through patronage.“ It started because people wanted to help; they wanted new music faster. So their name goes up on the website, they get a receipt from the studio, a signed thank-you from me and a CD at the end. I certainly feel grateful.”

Be the first to comment on "Survival of the Fittest"