Electronic Music Foundation

Nick Krewen

GRAMMY.com

Sept 2002

Pierre Schaeffer, Luc Ferrari and Iannis Xenakis aren’t exactly household names in the world of commercial popular music, and the services the Electronic Music Foundation provides is unlikely to offer them any change in stature.

But they’re superstars in the world of avant-garde electronic compositions, and if you’re seeking out historical information or looking to hear and buy CDs of their pioneering work, the Albany-based EMF (www.emf.org) might be the best place to find it.

Pierre Schaeffer

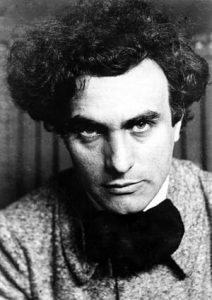

Luc Ferrari

Iannis Xenakis

Established in 1994 as a not-for-profit organization by Joel Chadabe, an American composer who led the development of interactive systems, EMF is helping to foster and preserve the innovative electronic avant-garde culture whose influence permeates today’s commercial music scene.

“The Foundation is not only about history, but about information and materials having to do with the non-commercial end of things,” says Chadabe, who serves as EMF chairman and president. He also holds concurrent positions as director of the Electronic Music Studios at Bennington College and the Manhattan School of Music. “We’re basically championing artists of interesting, cutting edge work.”

Joel Chadabe

In championing those artists through its website and other programs, EMF ascertains its role as more than just a time capsule: it serves as promoter (EMF Productions), publisher (EMF Media), publicist (ArtsElectric), software distributor (GRM Tools) and retailer (CDeMUSIC). It also provides listings for potential employment, grants, fellowships and other professional opportunities, and an Internet directory linking to other sites of similar interest.

Chadabe says he implemented CDeMUSIC after being stymied in the search of a work by one of his favorite composers.

“Back in the mid-90s when we started this, I saw a compact disc of Edgard Varèse’s Poême electronique,” Chadabe recalls. “I wanted to have it because it’s a classic. I was teaching, and I thought this would be really indispensable to play for classes. I looked around and I couldn’t find anyone who knew where to get it.

“I thought there was a real need for a distribution center for these niche materials. So we set up CDeMUSIC, which distributes compact discs, books and other items having to do with electronic music.”

Edgard Varèse

Suzanne Ciani

CDeMUSIC titles include such varied works as the angelic new age sonics of Suzanne Ciani, the contemporary electrobeat stylings of D.J. Spooky That Subliminal Kid and the modular synthesis of the innovative Morton Subotnick. But the melodically subversive compositions of the late John Cage and Iannis Xenakis receive equal billing, sampled by downloadable MP3s that offer a small window into the radical world of the avant-garde.

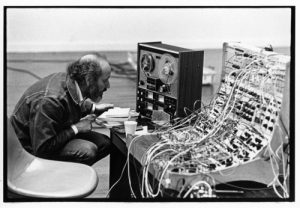

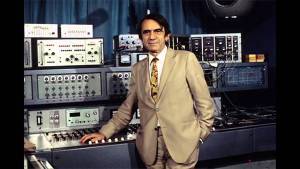

Morton Subotnick

John Cage, © Bob Cato

Although avant-garde sales are minimal – Chadabe says a bestseller may move 1000 copies in a two-to-three-year period – CDeMUSIC falls well within EMF’s supportive mandate.

“It’s really important to have for cultural and historical reasons, so that the material will not disappear,” says Chadabe.

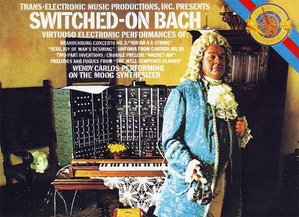

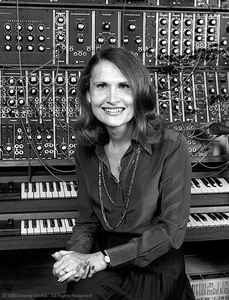

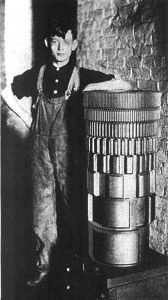

Although awareness of the synthesizer leaped into the mainstream conscience with the release of Walter (Wendy) Carlos’1969 classic million-selling Moog album Switched On Bach, electronic music has been with us since 1897 – the year inventor Thaddeus Cahill built a large keyboard instrument called the Telharmonium.

Switched-On Bach anniversary album cover

Wendy Carlos

Thaddeus Cahill and an early model of his Harmonium

The 20th century marked the rapid evolution of electronic music, through technological invention, compositional experimentation, recorded sounds and synthesis.

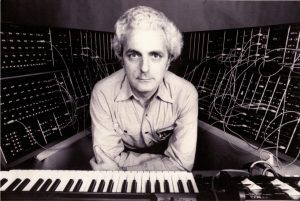

“What is the avant-garde today matures and grows into the mainstream,” notes Dr. Robert Moog, President of Moog Music Inc. and inventor of the world famous affordable brand of synthesizers that bear his name.

Moog, an EMF corporate sponsor who received a Technical Grammy in February for his lifelong achievements, says the foundation serves as a valuable outlet.

“People who are interested in experimental musicians are finding that they need something like the EMF to satisfy their needs as an alternate to the mainstream commercialization.

“It’s a service that encourages people who are doing the experimenting who in five, 10 or 20 years from now will be part of the mainstream music, but today are evolving. And nobody has to turn a profit at the end of every quarter.”

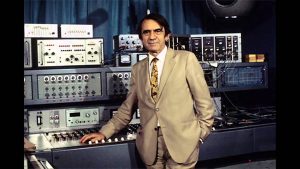

Robert Moog

William Blakeney

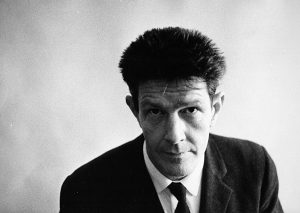

Hugh LeCaine

One of the EMF’s more intriguing projects involves Bill Blakeney, a Toronto lawyer and producer who restored and recorded works by composer John Cage, Canadian inventor Hugh Le Caine and others.

“It’s our folk music,” Blakeney notes. “We’re all post-modern kids. We’ve grown up on this stuff, and it’s part of our culture in some ways. Especially if you listen to the stuff that these composers did back in the 50s and ‘60s, it really is going back to our roots. We didn’t grow up typically in the Mississippi Delta, so this is our cultural heritage.”

Collaborating with executive producer Chadabe and co-producer and engineer Bob Doidge, Blakeney literally spends hundreds of hours in Hamilton, Ontario’s Grant Avenue Studios — famous as the headquarters where Brian Eno and then-owner Daniel Lanois did the crux of their ambient music exploration — recreating and remastering avant-garde classics for EMF Media.

Bob Doidge

Bob Doidge with Daniel Lanois

Brian Eno

“The challenge has been to restore them without coloring the sound,” states Blakeney, who has worked on an estimated 30 projects over seven years.

“Most of the analog restoration work is done under the supervision of Bob, and one of the great things about Grant Avenue is that it’s sort of a time capsule of older equipment. Most of the equipment that was there in the late‘70s is still in active service, plus it has fairly high-end digital facilities.

“Bob has a variety of different broadcast-quality analog decks, and a very good editor which is capable of doing 24-bit masters.”

Maintaining authenticity is the key.

“We take time to work with the composers,” says Blakeney. “We’ll do as many masters as are required in order to get approval, and that’s one of the reasons we’ve had such a good relationship with composers that work through EMF. We’re not cutting any corners. We’re trying to make it as authentic as possible.”

Recent restoration projects include the Cage compositions Birdcage and HPSCHD, the latter requiring seven harpsichords simultaneously performing seven different scores. Blakeney admits the work, which sometimes take two years to complete, isn’t easy.

“With HPSCHD, the technical requirements are staggering,” he explains. “It requires 72 tracks of digital audio, as well as 14 tracks of live music, so it’s a massive undertaking. Without the digital multi-tracks it couldn’t be done. And it has involved literally hundreds of hours of restoration of old tapes as well as doing live recordings of harpsichords at different locations. We try to keep them true to the analog originals.”

The challenges aren’t limited to the technical.

“When you listen to them hundreds of times at very high volumes, it does tend to scramble the grey cells,” Blakeney laughs. “ But on the other hand, the end result is really remarkable. They come up really sparkling.”

Blakeney says he and Doidge take great comfort in championing these composers as a labor of love, rendering a role unfulfilled by major record companies.

“A lot of the major labels are very fond of having composers like Cage, Xenakis and Ferrari in their stable of artists, but on the other hand the titles don’t traditionally sell in very large quantities. As a result, when it comes to mastering or restoration, it becomes a matter of economics.

“The projected budget for HPSCHD was something like $60,000 U.S. Essentially we were able to do it for a fraction of that just by being inventive and chaining the digital multi-tracks together.”

Noting that such pop icons as The Beatles, Pink Floyd and Frank Zappa were influenced by musique concrète forefathers Schaefer and Varèse, Blakeney says electronic music continues to influence the contemporary scene.

“I think we’re going through a renaissance of electronic music,” he explains. “DJ culture, and a lot of people working in experimental dance music have really gone back to the well. They’re sampling people like Xenakis and Cage and a lot of the great composers are being cannibalized. Some of it is very gimmicky, but others like Sonic Youth and DJ Spooky and Stereolab are real fans. They’re not ripping off the composers – it’s a homage. They really do appreciate the original stuff. They’ve educated themselves on it, and I think they’re trying to follow through on an evolutionary dead end. There’s a lot of great stuff out there.”

Joel Chadabe says you’ll find some of that stuff at EMF.

The more you’re interested in what’s conventional, and satisfied with what’s normal, the easier you’ll find things to be,” he states. “But if you’re looking for the real ideas, the exceptional things that fuel creativity, I think you would be interested in us.”

Be the first to comment on "Preserving Electronic Avant-Garde Culture"