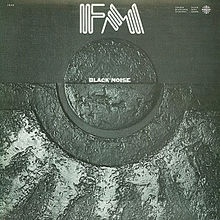

FM – Black Noise

Oh, the endless possibilities that can be stoked by science fiction.

It’s a realm where imaginations are stimulated, emancipated, and allowed to run wild; where boundaries are stretched and eliminated, and where the inconceivable can become an accomplished reality. It’s a topic that is so entrenched and valued in our society that sci-fi has gifted us with some of our most beloved cultural milestones, be they literary, cinematic, sculpted, painted, televised, or – in the case of Black Noise – musical.

In 1977, the year that the ambitious, timeless and innovative masterpiece Black Noise was conceived and delivered by Toronto-based violinist and mandolin player Nash The Slash; synth player, keyboardist, bass player and singer Cameron Hawkins, and fusion-influenced drummer and percussionist Martin Deller, collectively known as FM – the Star Wars movie franchise had just been launched and Star Trek had eclipsed its TV popularity several times over and was enjoying an unprecedented global run in syndication. Synth-driven, monophonic electronic music, especially in the context of pop and rock music, was still regarded to be in its infancy, although keyboard instruments themselves were on the cusp of polyphony (the ability to play more than one note at a time). Progressive rock, long presented in elastic, exploratory and sometimes rambling movements that emphasized sonic sculpture and lengthy solos, was turning a corner towards shorter, more economic compositions.

FM

Black Noise championed both worlds with a startling new sound that was both innovative and accessible; a lyrical voyage to the stars that sometimes wordlessly examined its surroundings, and expressed hope for the survival of a species at others.

From the plucked, reverberating ostinato of Nash’s space age mandolin on the classic and radio-friendly “Phasors On Stun,” through the glockenspiel-driven “One O’ Clock Tomorrow,” the warp-speed “Journey” and the epic three-movement opus of the title track, the eight-song album has been a touchstone of inspiration and resonance to the public and fellow Canadian groundbreakers, ranging from Saga and Strange Advance to rock superstars Rush, making for an impressive legacy.

There’s also a deserved sense of pride among its makers.

“We’re here 37 years later, still talking about this music? It’s astounding,” says FM co-founder Cam Hawkins.

“I’m impressed by the longevity. The fact that it still around, still sounds fresh, still makes sense. It doesn’t sound like it’s old pop or anything like that. In some ways, it had two essential ingredients: one was courage, and one was love. We loved the music that we listened to. We wanted to make that kind of music. We did it because that’s the music we felt inside us.”

Martin Deller, who contributed the stellar instrumentals “Hours,” “Slaughter In Robot Village” and co-wrote “Aldebaran,” says Black Noise was ambitious and encapsulated “a particular time full of heart and energy and commitment and youth.”

“It was done with a wonderful innocence, too,” Deller continues. “It wasn’t that we were jaded. This was the first big thing for all of us, and looking back, we’re proud of having done this record and what we were able to accomplish. Through the maturity of time, you can look back and say this was an important album. We’re happy that people are still really enjoying it.”

It was the beginning of something that would propel Nash, Hawkins and Deller into musical careers both individually and collectively that would touch people around the world.

Black Noise – the original indie cover

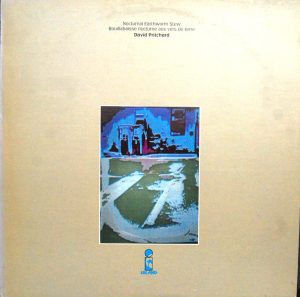

While the tangible FM story begins in late ’76 with the introduction of Cameron Hawkins to Nash The Slash, the band’s history actually pre-dates its existence, thanks to a trailblazing CHUM-FM DJ named David Pritchard and an album called Nocturnal Earthworm Stew.

Pritchard was an eclectic musician in his own right, using his bedroom as the studio laboratory to concoct his sonically adventurous soup. Aside from achieving the historic milestone of being the first Canadian album issued by Chris Blackwell’s Island Records, Nocturnal Earthworm Stew also features guest appearances by Nash The Slash, Deller and an uncredited Hawkins, although each of the participants made their contributions independently.

“It was a very classic example of an early independent,” says notes Deller. “David did it in his bedroom. I came in, played tracks, then he took them, flipped them upside down and had Nash play on them. Cam came in and played. None of us played in the session together.”

David Pritchard’s Nocturnal Earthworm Stew

Cameron Hawkins’ first real awareness of Jeff Plewman, a.k.a. Nash The Slash, was witnessing him perform in the band Breathless, the opener for Scrubbaloe Caine at the Ontario Place Forum, a much-missed venue noted for its circular, rotating stage and unobstructed sightlines.

“There was this maniac out there on the violin, who, for a finale, blew a flame out of his mouth and set his violin on fire,” Hawkins recalls.

“Some of those flames fell off into the audience, several of whom jumped up and patted themselves out.”

Hawkins was neither impressed nor amused.

“I thought it was disgusting,” he recalls. “That’s not music – it’s theatre. I’d never play in a band like that.”

But Nash was all about the performance art: aside from his Breathless commitment, Nash had taken up residency at the Roxy Theatre located on Danforth Avenue, where he also lived in an apartment behind the projection room. His legendary one-man shows found him dressed in a top hat and a tux, composing his own soundtracks to silent films.

Obviously, Hawkins’ curiosity was piqued. He invited Nash, whom he remembered was sporting “long, curly blond hair,” to sit in on a video shoot with Hawkins’ current band Clear. Later, the duo hightailed it back to Nash’s Roxy apartment – heavily decorated with Mike Hammer horror film posters – and over the course of the next six months, wrote some of the seminal songs that would appear on Black Noise: “Phasors On Stun,” “One O’Clock Tomorrow” and “Black Noise.”

Nash the Slash

The duo worked their magic on a Mini-Moog, an Elka Rhapsody string machine with a set of bass pedals, a sequencer and an analog synthesizer “that could repeat up to 16 notes endlessly,” Hawkins recalls. Nash provided his stringed menagerie consisting of the violin, the mandolin, an Echoplex and a drum machine that Hawkins remembers had settings like “Bossa Nova” and “samba.”

“Nash could turn it into a “thunder machine,’” marveled Hawkins.

“The string machine kind of sounded like a wheezy organ, but if you triggered and filtered it and plugged it into the Mini-Moog, and played the notes on Mini-Moog of what I did on the bass, you anticipated what polyphonic could do.

“So for a very brief period of time, we took a bit of an ingenious approach and it was what made us stand out. We also let the capabilities of the technology write the music. So we’d have songs that were at least five minutes long – sometimes, twice as long – and whatever Nash was playing on the Echoplex would loop around so we’d actually get two Nashes playing live on stage.

“We weren’t really following any rules, except for one: what sounds was the technology telling us to make?”

When it came to performance, Nash — still four years away from adopting the mummified bandage look that would become his trademark – schooled Hawkins about showmanship.

“I learned a lot from Nash about the performance side,” Hawkins acknowledges. “It’s not just what people hear, it’s what they see: It’s about the show. For the first six months that Nash and I wrote those songs, it was just hard work making music. But when we did shows, there was a rear screen that projected movies and slides…it was important to entertain people as well as play them good music.”

FM

FM, named after radio frequency modulation at a time when it was most experimental, continued on as a duo, appearing on TV Ontario’s NightMusic with host Reiner Schwarz and booking a three-night run at the A Space Gallery on Richmond St., where a multitude of Canadian record company A&R reps, those emboldened with the power to sign new acts, witnessed their show, heaped praised upon them and promptly told them that they wouldn’t be contracted to any deal unless they incorporated a drummer.

“Nash and I thought that was a fair assessment,” Hawkins recalls.

Enter Martin Deller, an accomplished stickman with a jazz pedigree who had a weekly gig with a blues band called Cueball and occasionally sat in with Hawkins and Nash. He passed the FM litmus test by proving he could complement the metronomic and rudimentary drum machine rhythms, as well as injecting his own persona into the mix.

“I remember when we were doing ‘Dialing for Dharma’ and that song features a sequencer. And I remember them thinking, ‘oh, how is he going to react to this?’ I walked out of the booth and both Cam and Nash had an ear-to-ear grin, going, ‘well, he fucking nailed that one.’”

After Deller joined in early ’77, the next six months were spent playing clubs around Toronto and quickly establishing themselves as a must-see act. It should be noted that the 1970s was a sensational decade for working musicians: the club scene was healthy, and bands would enjoy six-day residencies in most taverns that would enable them to practice in front of an audience, hone their chops to impeccable standards.

Returning to the A-Space run for a moment, there was one other audience member who would prove to be an important catalyst in getting FM into the studio.

Keith Whiting had recently arrived from England and his producer position at Decca Records, bringing with him future Juno Award-winning engineer Mike Jones in tow. Whiting was about to preside over national broadcaster CBC Radio’s recording division.

CBC Records, however, was unlike any other record company, in that its federally-mandated purpose was not to compete with other labels, but chiefly providing programming for CBC stations across Canada.

How it worked: usually a jazz or classical act would be booked at a CBC recording studio, cut three or four songs that would be compiled onto an anthology, and then that anthology would be issued on a minimum pressing run (averaging 500-1000 copies) and distributed for airplay, with a few copies left over for potential mail order sales.

Whiting, who had served as an assistant engineer on No Answer, the debut Electric Light Orchestra album, and a producer for Dusty Springfield and many others, was hooked from the moment he witnessed the FM experience.

“I was knocked out with it right from the start,” Whiting recalls. “As soon as I got an opportunity to do something with them, we did. They were good musicians and they had that material for a while.”

Whiting remembers an FM audition tape floating around the CBC, which helped expedite the sessions. He also went a few steps further than his predecessor Hedley Jones, who was also very aware of FM: not only did Whiting feel that the trio deserved an entire album of their own, but he also successfully argued with his superiors that FM deserved more than what the antiquated CBC recording studio equipment could provide.

“FM brought Marty Deller on; we got a small budget from CBC, booked Sounds Interchange (on Adelaide Street) for a week and did the album,” Whiting remembers.

FM

Actually, it was a tad more than a week, but even at 10 to 12 days – eight for recording, two for mixing – there was no room for error. As Whiting recalls, however, FM was up to the task.

“The sessions were quite frantic,” Whiting recalls with a laugh, noting that the “record” button was pressed at around 2 p.m. each day and that the sessions would conclude sometime around 6 a.m.

“We put in really long hours, and it got pretty crazy. To let off steam in the middle of the night, we’d have ‘bog roll’ fights: we’d go around the studios throwing toilet paper rolls at each other at 3 a.m. You couldn’t do too much damage,” he chuckles.

The vestiges of time have impacted the associated memories of those involved to recall exactly which song was the first to be worked on, but Keith Whiting does remember the sessions pretty much sailing along without too many glitches, mainly due to FM’s solid prep work.

“The band had played around the Toronto scene as a three-piece for about six months and the songs were for the most part, worked out,” Hawkins remembers. “Marty and I would rehearse, just the two of us without Nash, to make sure that we got the bed tracks right.

“Plus, we were in our mid-20s, so the sessions were spirited: we knew that we were getting the opportunity that we were looking for. We had a lot of fun recording the record.”

However, there ended up being one major hitch that ended up shocking both Hawkins and Deller. Cameron Hawkins picks up the story…

“I was playing pinball at the studio to let steam off, and someone came in and said, ‘Cam, it’s time for the synth solo in “Slaughter In Robot Village”’, which is one of Marty’s songs.

“And I said, ‘I don’t have a solo in “Slaughter In Robot Village” – Nash does.’ And he said, “You do now, because Nash has left the band.’”

According to Hawkins, Nash’s departure was triggered by a combination of factors: the frustration of repeatedly tuning a mandolin paired with a testy engineer who kept fooling around with the Varispeed control on the analog tape recorder.

“Tuning a mandolin is really hard, because you don’t just have four strings, you have eight strings in pairs, all tuned in unison,” Hawkins explains. “And mandolins are notorious for losing their tuning, so it was very frustrating for Nash. Mike (Jones) had apparently had it with what he perceived to be this prima donna musician thing, flipped the Varispeed up to its proper pitch, let the tape roll, and Nash came in, way out of tune. Nash got frustrated, put the mandolin down, and walked out.”

When Nash left, both Deller and Hawkins thought he was just blowing off steam.

“We’re thinking, ‘oh, he left the building. He’ll come back,” said Deller.

“He didn’t play with us again for six years,” adds Hawkins.

This cone of silence was apparently a Nash quality trait that would be repeated in later years.

“Nash was about moving on,” says Hawkins. “There were times when Nash needed the lift of having collaborators, and when he didn’t, would say, ‘I don’t need it now – I can go back to being Nash The Slash.’”

Deller suggested that the addition of a drummer to what had been a two-man set-up also troubled Nash.

“Nash had a vision when he was doing his solo stuff, and when he meets Cam, he says, ‘Ok, here’s a cool guy,’ and Nash can really easily still incorporate all of his vision. And then I come along, and it just changes it up again: I got the sense that, suddenly, three was a crowd for him, and along with all of that other frustration and pressure, he thought, ‘I‘ll just go and do it my way.’

“He was a very complex guy. He couldn’t maintain that sense of commitment to that larger thing. It seemed to be very characteristic through his career.”

FM’s Martin Deller & Cameron Hawkins

Nash’s lack of involvement with FM post-Black Noise was a conundrum that would later be solved by the addition of future k.d. lang producer and collaborator Ben Mink, but for now, everyone was enjoying the fact that the album sessions were complete and that everything sounded stellar.

“Keith got us in and out in 12 days within budget, made sure we were ready, navigated the politics within the CBC and made it fun to record,” Hawkins remembers. “In fact, we did the next record (Surveillance) with almost the same set up.

“I think that spoke to his success as a producer. He never got in the way. There’s a deft touch to that.”

After completing a stereo mix and a quadrophonic mix (the latter mix is still M.I.A. 37 years later, as are the album master tapes), Whiting and the CBC pressed up 500 copies of the album sporting a different cover than the publicly familiar Paul Till artwork.

Whiting, FM manager Malcolm Glassford and the band then shopped the disc to every Canadian and U.S. record company and heard…nothing.

Finally, Passport Records, a New Jersey based indie label specializing in imported British art and progressive rock, picked up the album for the U.S., and eventually distributed it in Canada through GRT.

But here’s the irony: the Canadian arrival of Black Noise in 1978 meant that it wasn’t the first FM album to be released domestically. In the time it took to secure a record deal, Hawkins, Deller and Mink had been afforded the opportunity to record and release Direct To Disc, an album that bypassed the usual analogue tape recording method and was cut directly to vinyl.

However, Direct To Disc, with its two 15-minute compositions, fell short of having the immediate impact of Black Noise, which received instant radio airplay due to the classic single “Phasors On Stun,” and eventually drove album sales to Canadian gold (50,000 copies sold) and probably platinum (100,000 copies) levels. (FM would be continually plagued by their numerous future record companies declaring insolvency, thus making the maintenance of accurate accounting suspect at the best of times).

This current reissue of Black Noise, lovingly re-mastered by Peter Moore (Cowboy Junkies) and distributed by Conveyor Canada on compact disc and digitally, is additionally significant for its bonus material: two live recordings and longer versions of “Phasors On Stun” and “Black Noise,” recorded at the defunct Larry’s Hideaway on Toronto’s Carlton Street a mere two weeks before the CBC sessions, are included here to offer a glimpse of the true depth of FM’s experimental nature. (The 180 gram vinyl version will be true to the original album release and not include the extra tracks).

“We had this jam sense,” recalls Martin Deller. “There was this wonderful element of improvisation. In classical music, you have something called the coda, which is a section added to the end of a piece where the soloist who is featured gets to riff on the themes of the composer’s music. FM would do this in the middle, so ‘Black Noise’ features this internal coda, if you will, where we go into the spacy section. That was a very appealing piece for all of us, and it was really apparent at this time.”

Because vinyl was limited to approximately 25 minutes a side back in the 1970s, Whiting was forced to condense some of FM’s arrangements.

“’Phasors’ used to have a five-minute spacy introduction with percussion and Nash making whispering sounds into a microphone,” Deller recalls.

“On ‘Black Noise,’ Nash is manipulating the drum machine, and we were still in the process of working out the arrangement.”

Adds Hawkins, “These two extra versions really offers people an insight into the real roots of the band: 10-to-15-minute explorations in real time with real inspiration. And these releases are dedicated to Nash, who passed away in May 2014, and whose spirit is definitely captured in these recordings.”

Still energetic, animated and passionate; still wonderfully cosmic and freshly imaginative for those who enjoy open frontiers and great music, the magical Black Noise remains a thoughtful gateway of – and to – the imagination, and the notion that the future has yet to be written.

“I thought it was pretty cool music,” says Martin Deller. “It was experimental music people would like because it had a melody. It was refreshing, it was rock and it had a jazzy element as well, which I think you can really hear on Black Noise, between the classical and the synth.”

For Cameron Hawkins, Black Noise symbolizes a call to action.

“To me, what it represents is the truth of a theorem: if you want to do something, do it. To me, Black Noise is something that is bigger than all of us who participated in the record. There’s always a benefit to creating.”

.

— Nick Krewen

Be the first to comment on "Liner notes: FM, Black Noise"