Canadian Music Week Guest Convinced Wall Street Financiers To Invest Millions In British Pop Star

By Nick Krewen

Special To The Star

March 2, 1999

David Pullman, who’s in town Thursday (March 4) at the Western Harbor Castle to deliver a keynote address for Canadian Music Week, is more magician than musician.

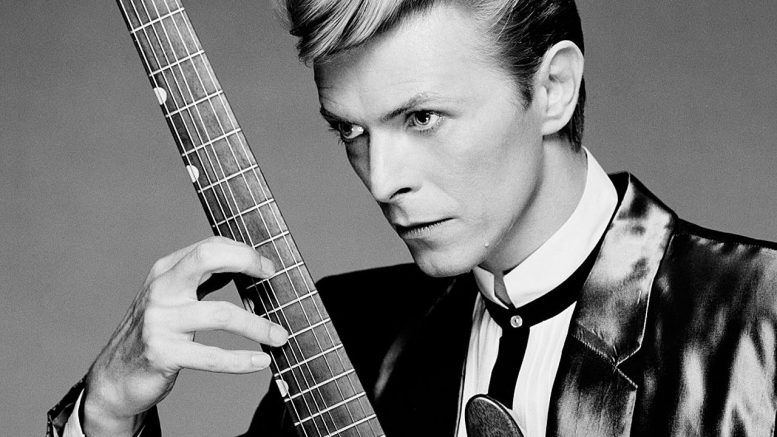

As managing director of The Pullman Group, he convinced stuffy Wall Street financiers to invest millions in David Bowie, or more specifically, Bowie’s intellectual property: his publishing inventory and projected future royalties generated by sales of his catalog albums.

As the creator of the nicknamed “Bowie Bonds” in 1997, Pullman not only obtained the British pop icon an instant $55 million U.S. tax-free winfall, but opened a new frontier on the asset-backed bond market that had been previously untapped.

Entertainment.

Previously, musicians, authors and other artists weren’t considered blue chip investments. But powerful Wall Street financial analysts Moody’s gave the “Bowie bonds” a respectable A3 — or A minus — rating, which Pullman brags “is on par with General Motors,” and New York-based Prudential Insurance snapped up most the 10-year corporate bonds for an annual 7.9% return.

Since the creation of the “Bowie bonds,” two more pop legends have inked similarly lucrative deals with Pullman, a keynote speaker booked to appear March 4 at this year’s Canadian Music Week at the Harbour Castle Hilton. Last year, Motown era songwriting trio Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier, and Eddie Holland (“How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You,)” “You Can’t Hurry Love”) cashed in to the tune of an estimated $30 million, while fellow Corporation songwriters and performers Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson (“Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” “Ain’t Nothing Like The Real Thing”) charted a $10 million payday.

Several others, ranging from The Rolling Stones and Crosby, Stills & Nash to Michael Jackson and Elton John are said to be considering similar deals to get their slice of an approximately $236 billion (U.S.) pie.

“It’s the wave of the future,” says the New York-born Pullman from the mid-Manhattan offices that bear his name.

Of course there’s a catch. Ownership of publishing, and to a certain extent record masters, is paramount. Also the minimum annual royalty flow Pullman will consider is six figures.

“It has to be someone who has consistent royalties, say $200,000 a year plus,” explains Pullman, 36, a Penn State and Wharton School of Finance graduate and track-and-field fanatic with a 14-year background in mortgage-based securities.

“Anything less wouldn’t make economic sense because there wouldn’t be enough to justify the transaction.”

It also helps to have a proven track record.

“The deal for Holland-Dozier-Holland, there’s a 38-year history,” Pullman explains. “And the deal for Bowie, the songs have 5 to 30 year histories.”

Apart from appealing to a musician’s notion that you can never have too much money, “Bowie bonds” ensure that the subject of the bond retains their ownership.

“I was talking with Bowie’s manager on some other business, and they were thinking of selling their catalog until I came up with this idea,” says Pullman, whose Pullman Group left Wall Street giant Fahnestock & Co. to go solo mid-summer last year.

Not only did Bowie get to keep the rights to the 25 of his 36 album catalog represented in the bond deal, but it was licensed to EMI for $30 million with the veteran rock chameleon securing his traditional cut of album sales. It’s an agreement that could have further ramifications in an age when new technologies such as the Internet are threatening record company and music publishing power bases.

“I think it’s probably a good deal for both sides,” says Harris Tulchin, a Los Angeles entertainment lawyer who heads Harris Tulchin & Associates and teaches entertainment studies at UCLA.

“I think it’s going to definitely have an effect on contract negotiations. There are going to be a lot of issues that are going to come up.”

Tulchin, has worked with gangsta hip-hop pioneer Ice Cube in the past, says record companies may try to negotiate a lower royalty rate to offset the increased frequency of royalty payments that would occur in a bond deal. But he also suggests it might be the artist’s opportunity to raise the ante.

“When an artist negotiates a contract, they’re going say, `If I get so big and so important that my royalties are going to be worth putting into a publically traded type of security, what am I gonna need?’ And at the same time the record company’s going to say, `Hey, if I’m going to give that type of security to an artist, what am I going to get back?'”

Pullman feels potential asset-backed bonds give artists added leverage.

“I’m just looking to use deals that will help songwriters and creators of intellectual property and entertainment houses keep them and not have to sell their assets to record companies or studios,” says Pullman, who keeps transactions private.

“In a lot of our deals I can find money by auditing record companies and studios and help the cash close our deals. We can use the leverage we have, because we’re doing so many deals of size for the artist. So this really empowers them.”

Not completely. There is a risk, although Pullman maintains it’s minimal, where the artist could lose their copyright if the loans default.

“The risk would be that if the bonds defaulted that the investors would have to take over the catalog and sell the assets to retrieve whatever was left in terms of value,” says Pullman.

“So if we did a deal worth $55 million and the catalogue is worth $70 million, it’s good. if it’s worth $40 million, it’s bad. But as the deals are self-liquidating, by the end of the deal there won’t be much left in the balance. And at the end of the deal, there’s no balance.

“We think we’ve structured the deal well enough so it won’t be a risk.”

Attorney Chulkin says the enormous costs of the potential bond deal should also be considered by artists.

Pullman is hoping to expand his horizons beyond music with “TV or film libraries, TV syndications, animation libraries,” and says he’s placed The Pullman Group in an enviable position as we enter the 21st century.

“Intellectual properties are going to be the largest market in the world over the next century, so it’s the ideal place to be,” he explains. “We’re actively moving from hard assets to intellectual property, and over this last century we’ve seen that that’s where all the great wealth has grown. So that’s where you want to be.”

Several veteran music industry figures seem to agree. Both ousted EMI CEO Charles Koppelman and Eagles impressario manager Irving Azoff have aligned themselves with finance companies in attempt to negotiate their own deals.

Pullman isn’t impressed.

“So far everyone and their brother has tried to copy us, and not one other party has done a deal besides me.”

David Bowie wouldn’t be one to argue. When his bonds mature in 2007, he’ll be laughing all the way to the bank again as the man who sold his world.