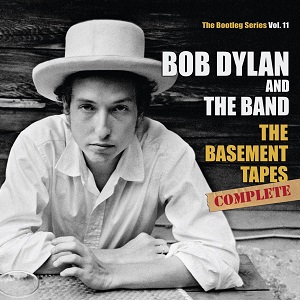

Toronto duo largely responsible for lifting the veil off “the most sought after and mysterious recordings from the post-nuclear, pre-digital era.”

Nick Krewen

Music, Published on Wed Nov 05 2014

Sitting at Johnny Rockets, a ’50s-style burger joint in Yonge-Dundas Square, my dining companion pulls out a cardboard envelope and hands it over.

“Open it up and have a look. Have a little whiff,” he insists.

Inside is a box containing a reel of recording tape, inscribed in marker with the following song titles in order: “You Ain’t Going Nowhere,” “Any Day Now — I Shall Be Released,” “If Your Memory Serves You Well,” “You Ain’t Going Nowhere” (Take 2 is written beside it in pencil), “I Shall Be Released” and two separate takes of “Too Much of Nothing.”

It takes a moment to sink in and realize what I’m actually holding: an original Basement Tape, one of the more than 20 reels recorded by Bob Dylan and the majority of Toronto legends The Band when Dylan was convalescing in Woodstock, N.Y., following a 1966 motorcycle accident.

How do I know it’s an original?

Because my dining companion is Toronto’s Jan Haust, Canadian music archivist, current curator of the Dylan-driven collection, and primarily responsible for the release earlier this week of The Basement Tapes Complete, a lavish six-CD set issued by Sony’s Legacy that finally lifts the veil off what Haust calls “the most sought after and mysterious recordings from the post-nuclear, pre-digital era.”

He’s not kidding. Music fans have been waiting nearly half a century to hear these recordings: 138 takes of 115 songs, all of them recorded informally throughout 1967 by The Band’s Garth Hudson, mostly in the cramped Woodstock-area basement of the abode known as Big Pink.

Jan Haust with Garth Hudson

Every note of such future Dylan-penned classics as “You Ain’t Going Nowhere,” “I Shall Be Released,” “This Wheel’s On Fire” and “The Mighty Quinn;” covers of well known and obscure songs like Hank Williams’ “You Win Again,” Ian Tyson’s “Four Strong Winds” and Johnny Cash’s “Belshazzar” has been lovingly restored and digitally remastered in Toronto by Haust and renowned Cowboy Junkies engineer and producer Peter J. Moore.

Prior to this week’s releases (there’s also a two-disc Sony edition of highlights called The Basement Tapes Raw), fans had received a limited taste of the Big Pink sessions, including the official 24-song The Basement Tapes and a few tracks that have surfaced since, mostly notably “I’m Not There” from the 2007 Todd Haynes film of the same name.

The Basement Tapes sessions were significant for a number of reasons.

First, the relaxed atmosphere of everyone crammed into an intimate space allowed Dylan (who performs at the Sony Centre on Nov. 17 and 18) to explore another songwriting direction, which was a little more laidback and humorous.

“What was going on for the most part, pretty basic,” recalls Hudson, who set up the basement with microphones, a recorder and a mixer, in a separate phone interview.

“He (Bob) would write the song upstairs, couch and coffee table, then take it down and we would play it, and usually, not even run through it once. We’d do the introduction and then a bit of the song and then I would put the machine on record.”

Some argue it may have been the birth of alt-country, but a bigger significance is that it completed a musical coming of age.

“It’s where it all ended up coming together,” notes Haust. “And that’s the fascinating component here. The basement is the incubator of what became The Band.”

The Band

For Haust, the release of The Basement Tapes Complete marks the end of a 12-year journey for him and Moore, the engineer. The duo first heard the tapes, through an arrangement via Haust’s friendship with Hudson, when Robbie Robertson was assembling 2005’s The Band box set A Musical History.

“Some of the tapes were in rough shape, through no fault of Garth Hudson’s and through no fault of anyone’s,” Haust recalls.

Several reels were mouldy and Moore had to delicately unwind and re-spool some 1,800 feet of “very, very thin” reel-to-reel tape by hand on a few others to “flatten them out.”

There was also a bigger challenge: all the songs were recorded on a rare quarter-track machine with such poor quality tape that Moore didn’t have the equipment for proper playback, let alone restoration.

“These tapes were never meant to be heard by the public,” said Moore in a separate interview. “These were sketches — the jotting down of ideas. So the tape’s speed was 7½ inches per second, where most of your quality pro recordings are at 30 or 15 inches per second. I told Jan, there’s no such thing as a professional quarter-track machine.”

So Moore had to get a playback tape head custom made for his own equipment and found a New Jersey manufacturer who had the expertise to make it. The request was so rare that the manufacturer, Jim French, had only built one prior to Moore’s request.

The buyer? Neil Young, known for being quite persnickety when it comes to technical recording tools.

“Once I heard that, I knew I was following the right logic,” Moore says.

When Dylan’s manager Jeff Rosen and Sony Music finally commissioned Haust and Moore to assemble The Basement Tapes Complete, the duo huddled in Moore’s studio from March through September, deciding to follow Garth Hudson’s original lead and sonically restore what was going on in the basement.

“We kept the integrity of what Garth envisioned,” says Moore. “I didn’t add reverb or anything to these tapes. I’m phase correcting — not changing the picture, just realigning the lens.

“But when you realign the lens, all of a sudden you have that much more depth of field. I phase corrected a lot of the tapes and suddenly the bass appears. You’re actually hearing the bass for the first time — Rick (Danko) and his lovely melodic glissandos and everything he’s doing on that bass.

“Whereas on the bootlegs, there’s no top end, no bottom end, just more of a whiny mid-range. I’m bringing it into focus.”

The sound is immaculate, even impressing the man who commandeered the original tape recorder, Garth Hudson.

“I remember the sounds very well, the background sounds and the instruments,” Hudson says. “What we have now is clarity. It was a lot of work on Jan’s part and Peter Moore with his incredible talent. The voice is more alive. It’s clearer. And Peter has also assembled and revived tape that has been crinkled, stretched. So it’s been a big process.”

Now that The Basement Tapes Complete has finally seen the light of day, Haust and Moore have one more ambitious project in mind: an eight-CD, DVD and book box set chronicling Levon and The Hawks, dating back to their individual pre-Ronnie Hawkins musical pursuits in the late ’50s.

In the meantime, Haust will savour the arrival of The Basement Tapes Complete.

“I’m pleased as punch that we were able to put it together,” says Haust.

“This is the first time ever that a Bob Dylan project was produced in Toronto. That’s very significant. It’s four Canadian rock ’n’ rollers and an American folksinger. Now we’ve set the record straight. . . .

“We have cleaned up these recordings. We have repaired the damaged tape. We have treated these 47-year-old recordings like the archaeological gems that they are.

“This isn’t the Mona Lisa. These are the sketches.”

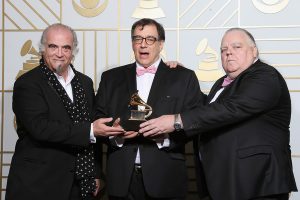

Sony executive Steve Berkowitz, Jan Haust and Peter J. Moore receiving a Grammy for their compilation and restoration work on Bob Dylan: The Basement Tapes Complete

Bob Dylan and The Band’s complete Basement Tapes resurface at last | Toronto Star

Be the first to comment on "Bob Dylan and The Band’s complete Basement Tapes resurface at last"