Nick Krewen

Special To The Star

Saturday, April 10, 1999

Money, guns and “hoes.”

If you’re aware of any semblance of hip-hop culture, you’ve heard it all before: the tired rap clichés where men brag about the numbers of dollars in their bank accounts, the inexhaustible supply of women wilting at their sexual prowess, the impressive numbers of corpses they’ve plowed through during gang shoot-outs.

Yada yada yada.

While there may always be an audience for the tough-talking, Uzi-toting “gangsta” rap of Earl “DMX” Simmons or the more recent graphic “horrorcore” of shock rapper Marshall “Eminem” Mathers, the recent ascent of Grammy queen Lauryn Hill, Atlanta’s innovative OutKast, Lyricist Lounge graduates Black Star and Philadelphia’s instrument-playing The Roots suggest that a new conscience is emerging, that the tide may be changing.

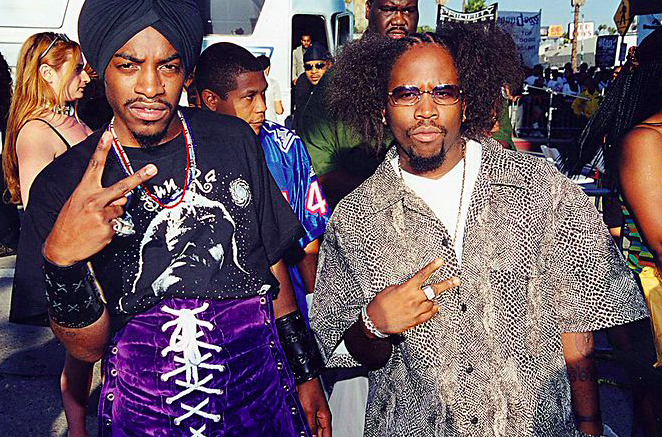

“Definitely,” agrees OutKast’s Andre “Dre” Benjamin, whose recent album Aquemini is at the forefront of the revolution.

“What I think it’s all about right about now is change, you know? Right now hip-hop is expanding and looking for things.”

“Hip-hop is in a state of constant evolution,” echoes Danyel Smith, Editor-In-Chief of VIBE, the popular African-American culture magazine founded by Quincy Jones that boasts a 700,000 circulation and a monthly readership of 4.3 million.

However, despite a recent outbreak of “conscience rap” recordings by Goodie Mob, Brand Nubian, Black- Eyed Peas, and imminent releases of albums by noted hip-hop thinkers Kris “KRS-One” Parker, Gang Starr and the April 6 street date of NAS’ I Am…The Autobiography , Smith stops short of calling it a trend.

“Between Lauryn Hill and The Roots and Erykah Badu, I guess that could be true. There are always trends,” argues Smith.

“I hate trends, and I hate participating in defining them, because I think they’re illusory. I feel like they all co-exist and you can pick what you want to pick.”

Jermaine Dupri, recording artist, red-hot producer of TLC, Usher and MA$E and CEO of his own So So Def Recordings is even less convinced that there is a movement.

“Maybe they’re having a better year than they’ve ever had, but it’s been around,” says Dupri, in Toronto recently for his first film role for In Too Deep .

“I’ve always seen those types of groups as I’ve been coming up.”

Dupri, whose production role has helped acts sell more than 20 million records in the past eight years, recalls the late ’80s and the days Long Island’s De La Soul and The Jungle Brothers. But he says today’s kids are ignorant of the pioneers and uninterested in history.

“The young kids don’t care,” says Dupri. “It’s sad. You’ve got a whole new generation of hip-hoppers like little kids that don’t really know about it and don’t really want to hear about it. To the generation growing up now, Master P. is their RUN-D.M.C. Old school rap for them is Kris-Kross – that’s seven years ago. Afrika Bambaataa — that’s old school for me. There are generations of it.”

Still, it’s hard to ignore the creative and commercial signs that something new is afoot.

On The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill , the New Jersey-based Fugees singer rhapsodizes about her carefree impoverished African American childhood on “Every Ghetto, Every City,” a far cry from the violent hustle ‘n’slum mentality painted by old school rappers:

“Springfield Ave. had the best popsicles/Saturday morning cartoons and Kung-Fu.”

Another rarely covered topic: the joys of motherhood on “To Zion,” a tribute to her young son by Rohan Marley.

“Unsure of what the balance held/I touched my belly overwhelmed/By what I had been chosen to perform.”

This refreshing diversion from the often macho, misogynistic, violent and vicious world of rap has struck a chord with record buyers: The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill has spent most of the past 27 weeks near the top of Billboard Magazine‘s Top 200 Retail Album sales chart, moving an impressive five million copies.

VIBE’s Danyel Smith insists that Hill’s appeal extends beyond hip-hop audiences.

“She’s a universal phenomenon,” says Smith. “I don’t think it’s because she’s a woman or because she’s black or because she’s a hip-hop star. I think people respond to her because she trembles with a real serious kind of truth that people respond to, and that works for whatever field you’re in, whether you’re a movie star, an emcee, a politician — whatever. If you ring with truth, you win.”

But Hill isn’t the only artist offering an alternative outlook.

On “Return Of The G,” the opening salvo of OutKast’s Aquemini , members Big Boi and Dre take one of the more amplified male rap icons — the “gangsta” — to task for shirking his parental duties:

“Gangsta niggas who got them kids, who got enough to buy an ounce/ But not enough to bounce them kids to the zoo.”

“The times are thrown in there because it’s a part of the community. That’s what it’s all about, so we’re going to talk about it,” explains OutKast’s Benjamin, who created the acclaimed Aquemini with partner Antoine “Big Boi” Patton. The album has sold more than one million copies in the U.S., bolstered by the current radio hit named after and inspired by ’60s civil activist Rosa Parks.

“‘Return Of The G’ came from going around our neighbourhood and seeing people not taking care of their responsibilities,” he said recently from a New Orleans tour stop.

Benjamin says he’s somewhat sympathetic to the chest-puffing antics of the thug, but it’s time for them to snap into reality.

“We understand. You want to be a regular man out there. You don’t want to be in no trouble — you’re just trying to chill. But in society, you’ve got people who want to take yours to get theirs. You have to protect yourself.

“Nowadays, we’ve got kids so we got to be here. We understand if you’ve got to put your gangsta-face on sometime.”

The fact that “Return Of The G” is such a slap to the seemingly unassailable hoodlum isn’t lost on OutKast.

“Right now, people are caught up in doing the formula,” Benjamin reasons. “People are sticking with that instead of stepping outside the lines and trying it with new ingredients.

“We wanted to make something that will last forever. We don’t want it to be an album where you groove at a party one night, and next year it won’t mean nothing.”

The Roots’ new Things Fall Apart and Mos Def & Talib Kweli are Black Star also venture to new lyrical places, although arguably the symbolic touchstone of this creativity is Hill. In an August interview with VIBE, Hill outlined her manifesto to “empower, inform and inspire.”

“I think people tend to underutilize hip hop,” Hill said at the time. “I think hip hop can bring our agenda to the front, but we talk about a bunch of nothing rather than real issues. Hip hop has the potential to be a great forum.”

OutKast’s Andre Benjamin says key is individuality, to resist the temptation to run with the pack.

“I think it’s not being scared to venture out and try new things. Don’t do it just because somebody else is doing it.”

However, Jermaine Dupri is fatalistic about any longterm interest. Audiences are too fickle.

“The hip-hop community looks for the next flavor of the year, every year,” states Dupri. “So you have to continually make yourself new to the public over and over again. That’s the whole thing about this business. You’ve got to continue to make yourself fresh.”

And when it ends, Dupri knows the barometer he’ll be using.

“The sales,” he says. “I judge everything by sales. When it stops selling, it’s over. It’s time to move on, and give them something else to go buy.”