NICK KREWEN

Mike Oldfield, the British composer of Tubular Bells, the chart-topping 1973 instrumental album that revolutionized rock music and represented progressive rock at its most indulgent, sees future music entertainment as “a Salvadore Dali painting you can walk into.”

Limited copies of his new album, Songs Of Distant Earth, contain a multi-media CD-ROM that he assembled midway through recording sessions, and Oldfield says he’s excited by new computer technology.

“I want to create a new form of entertainment,” says Oldfield, 41. “I need that new challenge.”

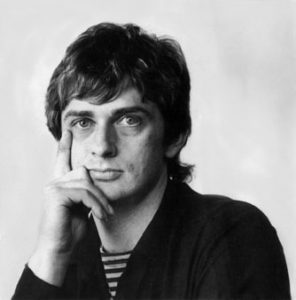

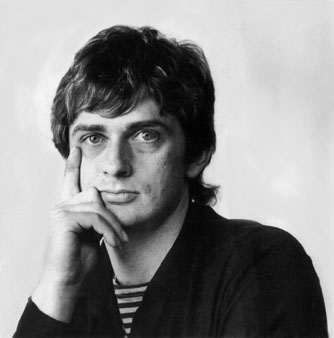

Mike Oldfield promo photo circa Crises

Oldfield has his own recording and graphic studios just outside London where he lives with his girlfriend, and says music on its own no longer holds a challenge for him.

“I’m interested in working with creative people in fields other than music,” says the father of five. “I’m interesting in shaping worlds that are beyond simple animation or movie-making. I’m more interested in the kind of interactive quest of finding your way through these worlds. That’s my plan.”

A master multi-instrumentalist who has released 19 albums, the Reading-born Oldfield started his career at the age of 14 in Sallyangie, a folk duo formed with his sister Sally Oldfield that released one album in 1968.

In 1970, he played bass and guitar with former Soft Machine member Kevin Ayers before beginning Tubular Bells in 1971. Created over two years with Oldfield playing 17 instruments himself and recording countless overdubs, Tubular Bells has sold over 15 million copies around the world and stayed #1 on the British album retail charts for 18 straight months.

Adapted as the theme for the movie The Exorcist, it won a Grammy in 1975 for Best Instrumental and helped establish Virgin Records and entrepreneur Richard Branson‘s vast fortune.

Four years ago, Oldfield left Virgin and signed with Warner, releasing Tubular Bells II and two months ago, Songs Of Distant Earth, inspired by the science fiction novel of the same name by Arthur C. Clarke.

“I wanted to relaunch my career,” said Oldfield, who estimates his own album sales at 25 million copies. “The last few CDs on Virgin were just dumped out without any fanfare. I didn’t get along with them, and they wouldn’t let me go. It was a contract I signed when I was 20 and had lasted 17 years.”

Not all of Oldfield’s albums were long, instrumental opuses. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, he flirted with rock music, releasing Five Miles Out, Crises and Discovery. He even toured, making his only Canadian concert appearance in 1982.

But Oldfield says his rock days are now behind him.

“I’ve never been a stand up and rock-til-you-drop type of guy. It doesn’t give me a buzz. The first ten concerts are exciting. Then you think, I’ve done this before.

“Besides, commercial music in England is pretty uninteresting at the moment.”

Oldfield says he’s satisfied forging new paths into the creative frontier.

“I’m in the fortunate position where I no longer have to work for a living, so I can just sit here and happily feed my machines.

“I’ve got my niche. It used to be instrumental music, but now I’m tackling interactive video music. CD-ROMS are so boring, that I want to provide an alternative to opening a closet and seeing Prince in his underwear.”

PUBLISHED IN THE HAMILTON SPECTATOR Thursday, February 16, 1997

Be the first to comment on "Mike Oldfield talks Songs of Distant Earth"