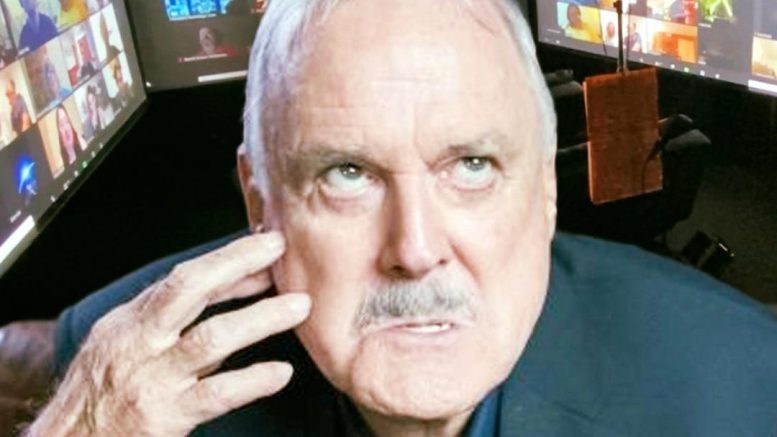

Cleese appears at Roy Thomson Hall on April 26 for “An Evening of Exceptional Silliness: Unique

Lives and Experience.”

By Nick Krewen

Special to the Star

And now for something completely different: John Cleese, how silly is your upcoming An Evening of Exceptional Silliness Unique Lives and Experience appearance at Roy Thomson Hall going to be?

Very, very silly or just semi-silly?

“I think semi-silly, probably,” responds the legendary British comedian and famed co-founder of the legendary Monty Python’s Flying Circus, speaking in early March from the other end a Zoom call from a tropical-looking location where I’d prefer to be.

“Because we’re not gonna do any stunts or get into costumes. My daughter (Camilla), who is very funny, is going to open for me for 15 minutes. Then I’ll come out and do 45 minutes or more. Then we will take questions from the audience, which is great fun, because you never know what people are going to ask you. And it doesn’t matter how well you write and perform the first half: people always enjoy the second half because it’s a bit chaotic and they like that.”

At 82, Cleese – who appears at Roy Thomson Hall on April 26 – is comedic royalty. Known for such iconic Monty Python creations as The Gumbys, The Minister of Silly Walks and “The Dead Parrot” Sketch, Cleese still possesses the ability to split ribs and leave his audiences rolling in the aisles with convulsive laughter due to his rather distinguished pedigree, not only with Monty Python (also featuring the now-deceased Graham Chapman and Terry Jones, and the still-breathing Michael Palin, Eric Idle and lone American of the group, animator and acclaimed film director Terry Gilliam) but as the principal of the madcap, 12-episode British series Fawlty Towers he created with his first wife, Connie Booth.

And that’s just a drop in the bucket: There was his 1988 Oscar-nominated box office smash A Fish Called Wanda co-starring Jamie Lee Curtis and Palin that landed Kevin Kline Best Supporting Actor and 1997’s Fierce Creatures, its-not-nearly-as-successful-follow-up-but-not-quite-sequel featuring the same cast; acting stints as “R” and “Q” in two of the Pierce Brosnan-led James Bond films – 1999’s The World Is Not Enough and 2002’s Die Another Day – the roles of “Nearly Headless Nick” in the 2001 and 2002 Harry Potter films The Philosopher’s Stone and The Chamber of Secrets; and “King Harold” in a trio of Shrek films during the 2000s.

There were also six episodes of U.S. TV’s Will and Grace where Cleese appeared as the character “Lyle Finster” and five on 3rd Rock From The Sun as “Dr. Liam Neesam” and he also makes a cameo appearance on Bryan Adams‘ new album So Happy It Hurts as the introductory narrator for the song “Kick Ass.”

Even prior to the Monty Python years – 40 TV episodes, 10 albums, three books, two video games (overseen by Toronto native Bob Ezrin) and five films (1972’s And Now For Something Completely Different; 1975’s Monty Python and The Holy Grail; 1979’s Life Of Brian; 1982’s Live At The Hollywood Bowl and 1983’s The Meaning of Life”) – Cleese’s formative years in the ’60s involved the Cambridge University Footlights Dramatic Club (where he met Chapman and The Goodies’ Tim-Brooke Taylor and Bill Oddie); The Frost Report on BBC1, which he co-wrote with Chapman (where he met Palin, Jones and Idle, as well as future British comedic legends The Two Ronnies, Marty Feldman and Peter Cook); ITV’s At Last The 1948 Show (star and co-writer) and as a writer for Doctor In The House.

With such impressive credentials, it seemed opportune to ask the Somerset-born Cleese, who earned a law degree from Cambridge and is currently enjoying life with his fourth wife, what makes for good comedy?

“I think seeing the truth under situations that are normally slightly camouflaged,” he responds. “Do you see what I mean? If you can say what people are thinking, but not saying…that’s always very funny. Because if there’s an element of anxiety about what you’re talking about, you get bigger laughs. You not only get the laugh, but you get extra energy in the laugh from the anxiety being released.

“For example, I talk quite a lot about death in my show and people go a little bit tight when I start, but by the end they’re laughing their silly heads off and feeling better about the prospects, too,” he explains. “There’s something about saying things that everybody’s thinking that’s a key to getting big laughs.”

Cleese said sketch comedy proved to be an excellent creative training ground to hone his skills, especially surrounding yourself with a team.

“I think whenever you’re starting, it’s very helpful to have people around you who are talented and to form a little band. If you get a good group of people, they learn from and support each other. There’s a bit of rivalry, but fundamentally, it’s like about a bunch of brothers or sisters: they quarrel with each other, but if anyone tries to attack them, they unify and repel invaders.

“If you’ve got a group like that, you get good. And I think one of the problems in is that the people who make the political and economic decisions don’t understand that kind of thing. “

Why did Monty Python work so well?

“Because we didn’t know what we were going to do,” he responds. “When we saw the head of entertainment at ITV, he said, ‘What are you proposing?’ And we couldn’t tell him. And he looked at us and said, ‘Go away and make 13 programs.’ He didn’t even ask for a pilot, because in those days, people used to trust their judgment. He just put his money on us and he got as a result a series that was outstandingly original.

“Most of the time, executives are trying to control things and saying, ‘well, what exactly are you gonna be doing? ‘And in that way, they already narrow the possibilities before the people have even talked to each other about what they’re gonna do. So, I have to think that we didn’t know what we were going to do was like walking into a beautiful field full of flowers and people saying, well, ‘just pick any you like.'”

One of this scribe’s all-time favourite films is the Python classic Holy Grail – and one of the standout scenes Cleese and partner Graham Chapman wrote for the film was epic the battle between King Arthur and the Black Knight whereby the latter loses all his limbs in a sword fight and still refuses to throw in the towel and admit defeat.

“It came from a story that I’d heard from a teacher, a man who taught didn’t bother to teach us much English, which was fine. because we spoke it fluently anyway,” Cleese recalls. “But he told us great stories, including one about a wrestling match that had taken place in ancient Rome, where the regular wrestlers had got incredibly entangled and suddenly, there was a loud crack.

“One of the men’s arms had broken under the pressure of the entanglement and the referee separated them, disentangled them and said to the guy with the broken arm,’ you know, go to a doctor and get that set immediately.’ He said to the other guy, ‘you won’…but the other guy was dead. And I’d always thought that was terribly funny.

“I told it to Graham Chapman one morning when we were making coffee. And the teacher had said to me, ‘it just shows that if you don’t give up, you can’t be beat,’ which I always thought was a very dodgy interpretation. But that’s why we wrote ‘The Black Knight:’ no matter how badly he was knocked about, he didn’t even notice. He wasn’t even disappointed when he lost an arm or a leg. We put that idea in, wrote the sketch and people howled with laughter at this man getting his arms and legs chopped off. It’s quite interesting to talk about that and say, well, ‘what enables us to laugh at it?'”

Despite Python’s popularity, the troupe found that it was difficult to get Grail funding, and it ended up being financed in part by British rockers Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull. And even though Grail, filmed for $400,000 (U.S.), offered a box office return of $5 million (U.S.), and – decades later – became the inspiration for the $175 million(U.S.) grossing Broadway musical Spamalot, the Pythons found it equally difficult to get backing for Life Of Brian.

“We couldn’t get anyone to give us the money,” Cleese remembers. “The only guy who would put the money up was George Harrison.

“Extraordinary – and I think it’s because creative people are much better at spotting creative possibilities than executives who’ve never actually written, performed or directed themselves.”

The film was a worldwide box office smash, earning $20 million and establishing Harrison’s filmmaking arm, Handmade Films (Time Bandits, Withnail and I.)

Alas, my 14 minute allotment to interview the comedian is up, and as he prepares to visit Toronto, which he says “is my favourite city but for one – Vancouver,” (he likes their harbours better,) John Cleese will leave our fair city exactly as he came: as the only comedian who has both a species of lemur and an asteroid named after him.

How have they impacted his life?

“Well, the first one I can tell you about: there was a very nice guy in Zurich in Switzerland and he contacted me one day and he said, ‘I’ve discovered a new species of lemur and this new species has been officially recognized by the body that does those things. May I call it after you?’

“And I was thrilled because I always like lemurs anyway. Funnily enough, when I was a boy, I was at a school which was right opposite a zoo. You literally walked out of the school and across the road was a zoo. And my favorite animal in that zoo was a ringtale lemur. And so, I said, ‘well, that’s wonderful.’ And he said, the lemur (the Bemaraha woolly lemur) will be called ‘Avahi cleesei” (pronounced a-vah-high cleez-e-eye.) That is the Latin name, for Cleese’s woolly lemur. And I’ve never been to Madagascar to see one because there are none in captivity. There are a small group of them on a lake in Madagascar. So, on my bucket list is a visit there.

“As for the asteroid (9681 Johncleese,) I don’t know how that happened. I think somebody just gave it to me as a gift without telling me and then people like you tell me about it. I know nothing about it.”