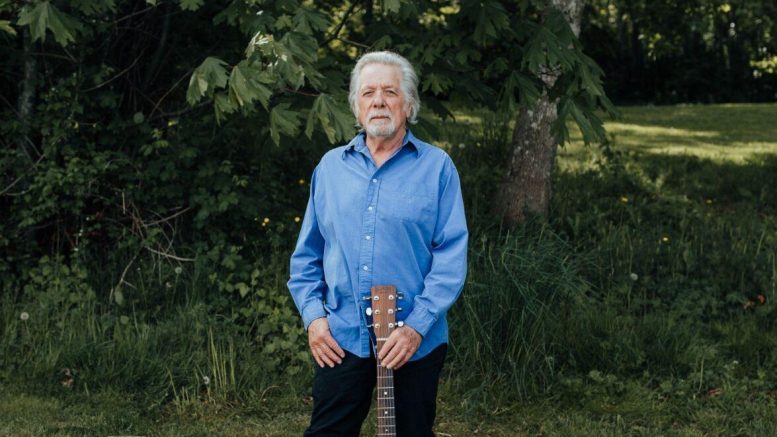

Materick, whose Canadian radio hits included “Linda, Put the Coffee On,” “Feelin’ Kinda Lucky Tonight” and “Northbound Plane,” will play Hugh’s Room Live on Saturday.

By Nick Krewen

Special to the Star

Linda, it’s almost time to put the coffee on.

When singer/songwriter Ray Materick performs at Hugh’s Room Live Saturday for the first time in over a decade, it will be with renewed interest in his most popular material, including the song “Linda, Put the Coffee On.”

In fact, the concert featuring Materick and his reunited Midnight Matinee band will focus on his 1974 to ’77 era, when the Brantford-born troubadour truly hit his creative stride. Blessed with a distinctive gravelly singing voice and a gift for prose that could be as introspective and romantic as it was rowdy, Materick released a trio of country-tinged folk rock albums through Warner Music Canada: Neon Rain, Best Friend Overnight and Midnight Matinee, which yielded such major Canadian radio hits as “Linda, Put the Coffee On,” “Feelin’ Kinda Lucky Tonight” and “Northbound Plane.”

“I really thought of him as more a poet than an artist,” said Gary Muth, the record executive who signed him to his first major label deal.

“His voice really wasn’t commercial for radio and it was hard to get around that, but his music, his songs, were excellent and that’s what really got me into it.”

Materick was certainly game: the son of a travelling, sax-toting evangelical minister who had led dance bands in the ‘40s and ‘50s, Materick had been influenced by his brother Ron’s rock band and the music of the Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Bob Dylan, Gordon Lightfoot and Kris Kristofferson.

He fronted a Motown cover band called the Chevrons for a bit, but spent most of his time trying to establish his uniqueness.

“I worked hard for many years to develop a sound that was original and songs with words that I liked,” recalled Materick from his Vancouver Island home. “I made a reel-to-reel demo in my brother’s basement, hit the bricks and eventually got a recording contract that got great reviews and a lot of airplay.”

The album was 1972’s Side Streets, signed to Kanata Records and nationally distributed by Ontario’s London Records.

Muth came into the picture after Kanata’s owner realized he couldn’t maintain the label. Muth didn’t need much convincing.

“In the ‘70s, you invested in an artist: not just one album, but for a career,” he said. “So I looked at it as, ‘Here’s a guy who could go the distance if we just worked with him’ and that’s exactly what we did.”

For 1974’s Neon Rain, Muth imported Bruce Cockburn producer Eugene Martynec, with Cockburn providing many of the album’s electric guitar solos.

“He provided some pretty mean guitar licks throughout,” Materick said.

Muth said they had a game plan and the next two albums were produced by Nashville-based Don Potter, also known for his work with jazz fluegelhorn player Chuck Mangione.

“Neon Rain was basically a continuation of late ‘60s, early ‘70s folk,” Muth said. “But then, if you go to the next one, Best Friend Overnight, it got a bit countrified. Don had a real vision of where music could go. He really countrified the whole thing and went on to produce The Judds after that.

“And then when we did Midnight Matinee, that was really a major work. Ray had got a lot more commercial and more comfortable in his voice. I’m sorry we didn’t get to do a fourth album, which we really wanted to but, at that point, Ray’s ego was getting in the way.”

Muth contends Materick was insisted on producing a fourth album himself. Muth gave him the money but said the result was less than appetizing.

“I said, ‘Ray, this is terrible. Look what you just did on Midnight Matinee and this is what you want to do now? No!’

“So we ended up parting ways on it. We could have probably gone on for another five years.”

Things didn’t go so well in the States, as Materick never found the time to travel to LA. as often as he should.

“The problem was, unless you’re sitting on their doorstep, not a lot happens,” Muth said. “What Ray should have done was move to Los Angeles.”

Materick also conceded that his lack of availability at Asylum Records headquarters in L.A. didn’t help his career south of the border.

“It was a different time in my life during that period where I had a brand new baby, so I traded it off to spending more time with my family then travelling,” he said.

After the Warner deal ran its course, Materick released a couple more albums with 1979’s Fever In Rio and a self-titled album in 1981, and then promptly disappeared. Years of coast-to-coast touring and dealing with the music business prompted a change of scenery and occupation.

“What got to me was the chaos and overall poor performance that these kind of omnipresent influences led to,” Materick said. “A travelling musician is exposed to so many moral and physical pitfalls, and it can be hard to keep your nose to the grindstone of creating and performing quality music. When it came to organizational priorities, everything began to look fuzzy and out of focus.”

Materick, who described his lifestyle in the ‘70s as “strictly a recreational drinker who smoked the occasional joint,” said he quit drinking to clear his head. He spent the next eight years as a woodworker in Toronto and loved it.

“As it turned out, another door opened up to a more relaxed and therapeutic lifestyle, and I was grateful for it.”

For a while, the woodworking gig satisfied him while he contemplated art and life.

“It was great,” Materick said. “It’s sort of the same thing as writing songs in a way: you have material; you have experience; you have the tools and you have a creative product at the end. So, it was a very similar but different use of my talent.”

But music was never far from his mind. He finally resurfaced at the turn of the century, independently releasing five albums in 2000 alone and another three by 2003, although those albums are largely unknown to his following.

He says it was by choice.

“I didn’t put much effort into publicizing it,” he said. “I just had to get it out of me, that’s all.”

Since then, Materick has largely been under the radar, resurfacing in 2003 for a double CD issued by Linus Entertainment that included his ‘70s material on one disc and newer stuff on the other; Hamilton and Toronto tribute concerts in 2012; and, last November, a Hamilton reunion of his Midnight Matinee band orchestrated by Bob Doidge, his former bass player.

It will be that lineup — with the exception of original guitarist Dan Lanois — that will take to the Hugh’s Room Live stage on Saturday.

“The show in Hamilton was a warm and wonderful experience,” said Materick. “It was so inspiring and so significant, and a real compliment to the music itself that’s stood the test of time.”

And it’s invigorated Materick, 77, one of Canada’s most undersung talents, to create more.

“Music was and is my main motivating force in my life,” he said. “I’m happy to say I am totally back in touch with my muse: writing and singing better than ever, and enjoying myself to the max.”