Published in the edition of Canadian Musician

TERRI CLARK

By Nick Krewen

Sometimes talent is only one aspect of the equation.

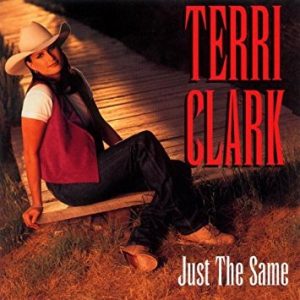

There’s no question that Terri Clark is a gifted country singer and songwriter: one who made enormous impact in Nashville with her self-titled debut album and a hatful of hits that began with the sassy, assertive post-break-up anthem of independence, “Better Things To Do;” and continued the momentum with an equally successful sophomore effort, Just The Same.

Two shots have netted bullseyes: two U.S. million sellers that have also reaped double platinum Canadian dividends, six Canadian Country Music Awards and a couple of Junos. Her radio successes have been driven by one remake — Warren Zevon‘s “Poor Poor Pitiful Me” — and even more self-generated smashes: “If I Were You,” “When Boy Meets Girl,” “Emotional Girl,” “Just The Same,” and “Something In The Water.”

She’s also a natural, earthy entertainer, whose delectable 5’11 frame wings across the stage night after night exhibiting goofy Canadian spunk, a healthy fun-loving attitude and a booming alto that can topple a can off a fence at 500 paces.

Do audiences adore her? When she appeared at Toronto’s Molson Amphitheatre this past summer, a standing ovation of ear-splitting cheers and thundering applause pre-empted her performance for five minutes.

Does Nashville’s Music Row love her? She receives frequent invitations to guest host The Nashville Network’s Primetime Country whenever emcee Gary Chapman can’t make it, and the superstars themselves are clamoring to land her as an opening act. In 1997, she hit the road with Texas icon George Strait. This year, it’s the one-two whammy of Brooks & Dunn and Reba McEntire, the latter a fan who will probably try to pick up a few pointers on Clark’s patented butter-churning move, The Blender.

Besides her obvious proficiency, Terri Clark could be the poster child for self-determination. She has not only dared to dream the unimaginable: she has made it happen. From the moment she saw Barbara Mandrell perform on the tube, she’s been transfixed, unwavering in her vision. Yesterday, she was longingly watching idols Mandrell, Ricky Skaggs and Reba McEntire on the television and hearing them on the radio. Today, she’s their peer.

“I’ve been on stage with Ricky Skaggs and Reba McEntire,” Clark tells Canadian Musician. “We’ve done that Primetime Country thing with Reba McEntire and Barbara Mandrell in the past. It was almost like an out-of-body experience. I would have died if I was 13. It’s a good thing I’m a little older and can now maintain my composure a little better. I’ve had some really thrilling experiences. I feel really, really lucky.”

Awesome.

Although Clark is largely responsible for her own odyssey, the country music seed was planted two generations earlier by her grandparents, Ray and Betty Gauthier. The Gauthiers were traditional Montreal-based singers who spent 50 years of their lives pursuing their own country carrot, opening for such legendary Nashville talents as Little Jimmy Dickens and George Jones whenever they crossed over to the Canadian side of the 49th parallel.

“I remember when I was really little, this guy named Dougie Triniere brought amplifiers and microphones and equipment over and set it up in the living room, where they’d let me sing into the microphone,” Clark recollects.

“I thought that was the coolest thing. Even before then, I’d spend a lot of time at my grandparents’ house, and my grandpa was playing guitar all the time. He’d sit in a chair for hours, and I’d just sit and watch. It was amazing to me that you’d make that sound come out of an instrument.”

Terri’s mom Linda taught her three chords at the age of 9, but it wasn’t until Clark was 15 that Barbara Mandrell’s weekly TV series cemented her future.

“She was obsessed,” recalls Linda Clark. “She was dedicated.

“We’re not talking a half hour a day or even hour a day. We’re talking hours! She’d come home from school for lunch, and the first thing she’d do is gobble down her lunch, go downstairs and get her guitar. If she had five minutes, she’d be playing something. Then after school, I’d be peeling potatoes and she would come up to the kitchen. She liked the acoustics because I had a big country kitchen. “She would play that all night and all weekend.”

For her sweet 16th, Terri’s father gave her a gift that has continued giving to this day.

“I got a Martin D28 when I was 16, and I still have it,” Terri says proudly. “It’s got tremendous sentimental value to me. I played it at Tootsie’s. And I still play it and write on it.”

Even at that young age, Terri Clark’s focus was clear.

“When I would walk to school, I’d case out the crescent I live in and figure out where I’d park the bus when I came home,” she remembers.

Between attending her Medicine Hat high school, working part-time in a Chinese restaurant and singing on occasion with Ron Larson and The Westerners, Clark scrimped and saved, shedded, strummed and sang with only one goal in mind: Nashville.

“I had a lot of encouragement from people around Medicine Hat,” Clark says. “Musicians around Medicine Hat really encouraged me to do that, and make that move. All of them said, `I wish I would have done that when I was younger.’ I thought, ‘Well, I’m not going to look back at my life at 50 and go, “I wish I’d have done that,” because it’ll be too late then. So I did it.”

She was barely out of high school when she made a beeline for Nashville, bound and determined to make it in a business that chews ’em up and spits ’em out with roto-rooter efficiency.

Within three days of arriving, Clark was hired to sing for tips at Tootsie’s, the famous watering hole next to The Ryman Theatre and The Grand Ole Opry.

“I played three days a week, and on a good day, I made between $25 and $30. I didn’t get rich,” Terri recalls. “But it was something that helped me develop my career and learn what real life was all about. I was still a kid raised in small town Medicine Hat, and I didn’t have much worldliness about me at the time.”

It was in 1989 that Clark met her future manager Woody Bowles, and the Nashville-based veteran former manager of The Judds, Moe Bandy and Baillie and the Boys – among others – remembers his first impression of the singer.

“Tom Long, who works for Balmur Music here now, was working for ASCAP at the time,” says Bowles. “Terri had come in to sing for Tom and let him hear some of her songs, and Tom called me and said, ‘There’s a girl here in my office I think you ought to hear sing.’ So I had her come right over. She sat down and sang for me, and she parted my hair with her voice.

“It was an amazing experience. She showed incredible potential as a songwriter from a very early age. She played guitar awesomely. She just sang incredibly, but she was so unique and different that I knew there was something there. I just knew it would take some time for her to allow it to mature, and for her to grow some.”

Bowles proposed to, as he describes it, act “like a guidance counselor” while Terri let seven months lapse on a previous production agreement.

“All I did was shine the light in the dark cave for her. She developed herself. I was the support system for her while she went through that process.”

Bowles hooked her up for some vocal coaching, and for songwriting refinement assigned her to writing sessions with Sue Patton at New Clarion Music. It also enabled Terri to hone her craft as Clark worked a succession of part-time jobs, including carpet cleaning, house painting, waitressing and as a bootseller.

“It was 1991 when Bryan Kennedy took her — he co-wrote “Honky Tonk Association’ with Garth Brooks – he took her in and cut five sides under a production deal with MCA Productions,” Bowles remembers. ” The demos were just a little too retro-traditional sounding, but he did an excellent job and we were able to shop her around based on that. On his efforts, we were eventually able to secure a publishing deal for her with a friend of mine, Gerry Smith, who had a co-publishing deal with Sony Tree at the time.”

Signed to Sony Tree for a weekly advance of $350 U.S., under the auspices of future Sony Nashville president Paul Worley, Clark says she considers her publishing her personal breakthrough.

“That’s where I really started to feel part of the music industry instead of a waitress wanna-be. I think when I was part of the writing process, being amongst the wheels turning every day on Music Row, I felt, ‘Yeah, I’m really in this and this is good.’ I was making some money at it. Not tons, but enough to live on.

“I can live on pretty much nothing. That’s the way I am. I don’t have a high cost of living. I’m just not into the fluffy lifestyle. When I started recording my songs, that advance came back out of that before I got any royalties. I had to pay it all back when ‘Better Things To Do’ became a hit. I didn’t see any money from the song until about a year ago, and that song’s two-and-a-half years old.”

Bowles explains that Clark was initially going to be the first artist to be signed by Worley to Sony Nashville when he assumed the A&R mantle in ’93, but circumstances and politics got in the way. Meanwhile, Keith Stegall entered the picture.

“Keith Stegall had been a big fan of hers, and had even used her to sing backgrounds on an album he was producing,” says Bowles. “I went over to see Keith one day, just to keep him updated on the demos she was doing and the songs she was writing, and he called me back into the studio and said, ‘Man, I have just accepted the position of VP of A&R at Mercury Records.'”

“I said, ‘Well, how convenient!’ says Bowles, erupting in laughter.

Within three weeks, Clark had her deal. The next 14 months were spent setting up the team: a business manager, the agency, the publicist, photo shoots, some media coaching, and a 10-city guitar pull with Stegall, Kim Richey, and Wesley Dennis that included Toronto.

“Better Things To Do” was released in July ’95, her band was assembled, and in August 1995 Clark played her first tour: seven Wal Mart parking lots in and around Houston, Texas.

“It was about 110 degrees in those parking lots,” Bowles says. “We finally referred to it as ‘The Asphault Tour.’ It was her ass, and my fault.”

The bouncy twang of “Better Things To Do” also announced the arrival of the emotionally independent female, something with which plenty of women could identify.

“I think that’s the thing that’s separated me in the beginning,” Clark says. “It was a little ballsier for a female, but I think I’ve got to be who I am. That’s how I express myself through music, and that’s a big part of my personality. I’ve got a very, intense passionate side, and it comes out that way. It wouldn’t be me if I did anything different. You have to be yourself or you’re not going to be able to pull it off.”

Although Clark’s star has enjoyed a rapid ascendancy, Bowles reminds Canadian Musician that the goals weren’t attained without some discomfort.

“Some days we were on the phone four or five hours just talking about what was going on in the business, how to walk our way through it, what was happening with other artists that were getting deals, people she knew that were getting deals faster, and why,” he recalls. “There was a lot of pain attached because she was turned down by every record label in town. But I think it made her a stronger human being. We’ve learned through this business that pain is necessary, and the misery part is optional.”

Bowles mentions a couple non-musical attributes that enabled Clark to persevere in the face of adversity.

“She had two real strong characteristics. One was willingness. The other was humility, which I define as teachability. She was teachable. I don’t mean moldable. She just soaked up every bit of information she could about the business and how it worked. She watched other artists that I was working with and learned from mistakes they had made. She learned from mistakes I had made. She and I had gobs of time to talk about career strategies and career philosophies, the type of people we wanted to surround her with.

“The other thing was the willingness. She was just willing to do the things that were necessary to get attention. Secondly, she was willing to go through the lengthy process without freaking out about the amount of time it would take.”

Although pleased by her career’s progress, Clark is only too aware that fame can be fleeting.

“I’m still not convinced I’m going to be able to keep it,” she admits. “It can go away at any point. But I think I’ll be able to do this for a long time. Regardless of radio airplay, I think I’ll always get to do shows if I want to because of what’s already happened.

“As long as I can sing and play, I’m happy. As long as somebody’s there to hear me, I’m happy. I was hoping it would come as far as it has, and when it did, it was a thrill. I feel very, very lucky.

“I can’t tell you when I exactly realized it. It wasn’t like I woke up one day and said, ‘Okay.’ It was very gradual. You have one hit, and then you have another one, and another one. Then pretty soon your 30 minute shows are starting to get really tight because you’ve got all these songs that everybody recognizes.

“I don’t know if I’ve ‘arrived.’ I try not to think about that too much because that’s where the ‘Big head’ syndrome starts to come in. I just do this for a living and have a good time, and I’m going to have a good time while it lasts, and do as much as I can while I can.”

The final word goes to Woody Bowles, who offers some good advice for aspiring musicians who have a desire to separate themselves from the rest of the pack.

“It’s really important for artists to be able to find someone who can kind of be their mentor through the process — someone they can really trust,” he says. “Terri came along at a time when I was managing Moe Bandy, and I was ready to pick up another act. The timing was just lucky on that. I think it’s real important for any of us to have somebody that we can turn to who is that one person we can go to for advice, and to talk through situations.

“The other thing is, if I’m going to be a winner, I’ve got to associate with other winners. It’s real simple.”

TERRI CLARK ON WRITING IN NASHVILLE

“I usually book appointments. When I write alone, it’s usually inspiration where it just hits me. I can not sit down at 10:00 and say, `Okay, I’m going to go in now and write a song by myself.’ It’s got to be something I’ve gone through, or that somebody else has gone through that’s inspired me to write. When I co-write, I just go into town and we usually come up with something .

“My favorite people to write with are Tom Shapiro and Chris Waters. We wrote “Better Things To Do,” “Boy Meets Girl,” “Suddenly Single” and “Just The Same.” We started writing together about three years ago, and we’ve written just about everything of mine. We have an incredible chemistry that all three of us realize, so we try to get together whenever we can.

“Scheduling usually works as follows: We book a 10:30 a.m., go to lunch about 12:30 p.m. Return about 2:30 p.m., and write til about 4:30. We probably spend six to eight hours on one song in total. As we write it, everybody pitches in, but Tom’s more of a melody writer. I set the groove or the tempo better. All three pitch in on lyrics. It’s a real good chemistry.”

TERRI CLARK ON LYRICS

“There’s certain parts of your life you don’t talk about. You’ve got to have a personal life. I think there are songs that every writer writes that’s either about them or somebody they know. I write a lot of songs that are about people that are my friends, not even about me. “If I Were You” is about a friend of mine. Regardless, it comes from personal circumstances. I wouldn’t want to reveal somebody else’s private matters. A long as the public enjoys it, they don’t need to know the exact details.”

TERRI CLARK ON PERFORMANCE

“I play a Triggs guitar: it’s a handmade custom job steely thing. I wanted the same bracings as Martin has, and I wanted the same sound. There’s a Fischman pickup in it, and it’s just an incredible sounding guitar when you plug it in. It’s got the unique, funky pick guard on it, and it’s got a bull head on top of the head stalk. It’s the same guitar I play in the “Emotional Girl” and “Poor, Poor Pitiful Me” videos. I play it on stage all the time. It’s become a little bit of a signature, I think.

“I had George Strait and Buck Owens both sign the back of it. I’m working on getting the legends to sign the back for me. I need to get Merle Haggard.

“I also have two Fender Telecasters, and I play a black Takamine. The Takamine has a full body sound, and I have to tune it down half a step for “Something In The Water” because we need two acoustics on that song. We use one of the Telecasters on “Stay With Me” — that old Faces song we do for our encore. We just put a bunch of distortion on it, and rock out. That’s fun. I think electric guitar is more cool. They’re edgier.

“I do four guitar changes throughout the show. I’ve got twelve guitars all together. A lot of them are at home.

“For singing live, I use a Shure Wireless microphone. It’s the same one that Clay Walker uses. Faith Hill and Tim McGraw use them. They sound really good. I haven’t had any problems. I’m not worried about it breaking down on me in the middle of a show.

“I use a different microphone in the studio. I think it’s a U84.”

TERRI CLARK ON VOCAL WARMUPS

“I don’t do any. I drink a lot of water, and that’s pretty much all I do. I do three or four songs at sound check, and that kind of gets my top end warmed up for the night. But I don’t really sit in the bus and go; “La la la la la la la”. I probably should.

“So far, it’s worked out great. I’ve only gotten a couple of colds where I’ve had to cancel a couple of shows, but I haven’t had any serious voice problems.

“I’ll tell you what’s helped my approach. Futuresonics ear monitors have helped a lot with not singing so hard. I think that’s the main clue as to not push too hard, cause that’s when you lose your voice.

“If I’m singing in the studio, I don’t have to strain to hear myself. I don’t need to scream. That’s what the microphone’s for. There’s a lot of years where I did push way too hard. I sang too loud. If I didn’t have ear monitors, I figure I probably would have had serious vocal problems by now.”

TERRI CLARK ON PLAYING FROM 25 PEOPLE TO 25,000

“I think my performance style really evolved quickly. I was forced to make it evolve. I was put on a stage that was huge, in the round, in front of 25,000 people a night with George Strait, and I had no time to run around on training wheels. I had to ride the bike! It did wonders for me as a performer and taught me a lot. I just get up and have fun because I think that’s what the people in the audience are there for. If we all have a good time then that’s the common goal.”

TERRI CLARK ON HER THIRD ALBUM, WHICH SHE’S CURRENTLY RECORDING IN NASHVILLE.

“I don’t think there’s a lot of difference between Terri Clark and Just The Same. The third album’s going to have some different stuff on it. I’m writing more introspectively now than even I did a year ago because of things I’ve gone through personally and professionally. You just grow as a person, and as you grow you mature. It’s definitely going to be showing up on the next record.

TERRI CLARK’S PHILOSOPHY

“I like to be really spontaneous. That’s how I go through life — by the seat of my pants.”