PUBLISHED IN THE CANADIAN COMPOSER, APRIL 1986

SURVIVING WITH RUSH

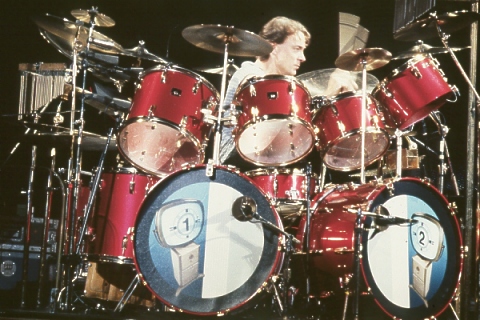

Drummer-lyricist Neil Peart looks forward

By Nick Krewen

The mark of longevity in the music business is originality. Usually, a band that lasts in this fashionably fickle marketplace does so by leaving an indelible imprint on audiences.

For the 12 years that drummer Neil Peart has been a part of Rush with guitarist Alex Lifeson and bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, he has made his mark with lyrics that challenge and probe far deeper than those attempted by many.

It’s no secret that the enduring success of this techno-rock-trio from Ontario is due in great part to Peart’s lyrical refinement.

Nick Krewen caught up with Rush in Tucson Arizona (a stop on their world tour to support their latest album Power Windows ), to talk to Peart about his forceful fusion of words and values.

Neil Peart

————————————————————————

NK: Will Rush return to its primary basic sound of its first few albums for any

upcoming studio projects?

NP: What for? The last thing I’m interested in is going back. I think that’s a

terrible thing. To get nostalgic about other people’s music, or even about

your own, makes a terrible statement about the condition of your life and

your prospects for the future. I have no patience with that kind of

attitude, whether it’s on radio or among friends.

For instance, I think that anyone who thinks that 1970 was the best year in

the world has a problem. For me, the older stuff just doesn’t have that

nostalgic appeal at all. I never have that feeling of ‘gee, I wish we could

recapture those magic moments,’ because those magic moments weren’t all that

magic, if the truth be known.

NK: Did your recent cycling trip through China inspire you musically?

NP: It’s too early to say. It certainly was one of the major experiences of my

life — just being thrown into a culture like that, and also being thrown

into it on my own, without the usual insulation of the group of friends that

I usually travel with. I think it certainly extended my world view, as it

were, although I already tended to try and think of the world as being a

much bigger place than the Niagara Peninsula or Canada, which many people

are wont to do.

I think what China had to offer, in terms of its impact on the world, I had

already taken advantage of in a song like “Territories” for instance. The

song was directly influenced by the Chinese attitude toward themselves.

The title comes from an area around Hong Kong called The New Territories. I

was struck by the sound of that word, and the territorial instinct. And what

with the Northwest Territories being part of Canada, it was just the right

sort of word to describe what I was after.

Also it had the right poetic sound and visual contact. That’s important to

me in a title. So that was the essence of it.

As for the opening line about the Middle Kingdom — that’s still what China

calls itself today. The reason for the Middle Kingdom is because it’s a

middle between Heaven and Earth. In other words, it’s slightly below Heaven

— but still above everybody on Earth.

That’s the way every person in every small town looks at the world, I think.

[They believe] The people they know and the little neighborhood they live in

is just a little bit more sane, a little bit more normal, and a little bit

more special than anywhere else in the world. That seems, superficially, to

be an innocent attitude, but in fact it’s that outlook that leads to racism

and nationalism, xenophobia and wars and persecution. Even as a kid in

school, if you were from one neighborhood as opposed to another, you were

considered an inferior subhuman. It seemed stupid at the time, and it seems

even more stupid now, when you come to see it continue into adulthood with

sports identification. If somebody wins something, it’s as if everybody in

that city personally won the Stanley Cup or the World Cup. It gets so

pathetic.

Look at what happens in England with the football riots; people murdering

because they support their own team. It’s the same thing that happens in

Ireland because of religion and in South Africa because of race. And it

happens in North Africa because of politics. Some people look at patriotism

or nationalism as being the next best thing to loyalty to your family. I

don’t buy it.

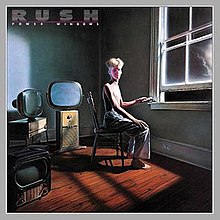

Power Windows

NK: Does the reference to ‘Middle Kingdom’ in “Territories” have any bearing in

“Middletown Dreams?”

NP: I used the exact thing which “Territories” warns against as a device in

“Middletown.” I chose ‘Middletown’ because there is a Middletown in almost

every state in the U.S. It comes from people identifying with a strong sense

of neighborhood. It’s a way of looking at the world with the eyeglass in

reverse.

I spent my days-off cycling around the countryside in the U.S., looking at

these little towns and getting a new appreciation of them. When you pass

through them at 15 miles per hour, you see them a little differently. So I

was looking at these places and kind of looking at the people in them —

fantasizing, perhaps romanticizing a little about their lives. I guess I

was even getting a little literary in imagining the present, past and

future of these men, women, and children. There was that romantic way of

looking at each small town.

But also each of the characters in that song is drawn from real life or

specific literary examples. The first character as based on a writer called

Sherwood Anderson. Late in his life, Anderson literally walked down the

railroad tracks out of a small town and went to Chicago in the early 1900’s

to become a very important writer of his generation. That’s an example of a

middle-aged man who may have been perceived by his neighbors, and by an

objective onlooker, to have sort of finished his life and he could have

stagnated in his little town. But he wasn’t finished in his own mind. He had

this big dream, and it was never too late for him, so he walked off and he

did it.

The painter Paul Gauguin is another example of a person who, late in life,

just walked out of his environment and went away. He too became important

and influential. He is the influence for the woman character of song.

The second verse about the young boy wanting to run away and become a

musician is a bit autobiographical. But it also reflects the backgrounds of

most of the successful musicians I know; many of whom came from very

unlikely backgrounds. Most of them had this dream that other people secretly

smiled at, or openly laughed at, and they just went out and made it happen.

NK: Power Windows seems to be an optimistic album…

NP: I guess it could be perceived as being uplifting or cynical, as can Grace

Under Pressure. A lot of people listen to “Middletown Dreams” and in their

interpretation of it, all those people fail. And it has been reviewed as a

song of bitter cynicism because I’m writing about people who are imprisoned

in small towns and who will remain there all their lives. But that’s the

total opposite of what my meaning was, of what my research shows and what

the reality of the song reflects.

It was written in the spirit of tremendous compassion and of tremendous

sadness and futility about human nature and what was going on at the time,

especially with the people who were close to me – watching the number of

people who were out of work; the number of people who had problems with

their health and their personal lives; people whose sensitivity was

disciplined by their environment. A lot of stuff in there were ingredients

of life as seen through the eyes and values of those people.

I have to be realistic and I have to see the world as it is, and the way

people really are. So it’s perhaps a cynical view of people while remaining

idealistic about life. That’s a hard line to walk and it’s hard to get

those two views to coalesce. But it’s the only way I can keep the values and

the goals I want in life and maintain the way of living that I want, while

at the same time staying in touch with reality and reconciling with what’s going on in

the world.

In “Marathon,” for instance, which is about the triumph of time and a kind of

message to myself (because I think life is too short for all the things that

I want to do), there’s a self-admonition saying that life is long enough.

You can do a lot – just don’t burn yourself out too fast trying to do

everything at once.

“Marathon” is a song about individual goals and trying to achieve them. And

it’s also about the old Chinese proverb: ‘The journey of a thousand miles

begins with one step.’

I try to keep a linear process of growth in a lot of different directions in

my life. A few years ago, when things were kind of overwhelming, I had a

sense of just treading water – trying to keep afloat in all of what people

were expecting me to do. Lately I have taken a lot more control of my life.

And I keep progressing steadily along five different avenues, instead of

trying to go off like a skyrocket in one direction.

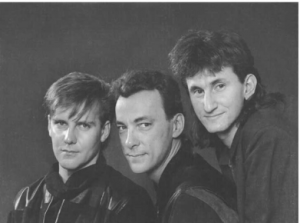

Rush U.S. promo shot

NK: What are some of the intangible rewards you’ve gained from your involvement within Rush?

NP: I think, first of all, to have survived is tremendously rewarding. I don’t

often stop and think about it, but when I do I’m reminded again of the quote

from the song “Marathon:” “First, you’ve got to last.” That was the motto of

one of Napoleon‘s marshalls.

It was later adapted by Ernest Hemingway. As a writer, Hemingway thought that

the most important thing was to sustain a reputation and integrity.

Hopefully, all of the other fruits would follow from that. And for us as a

band, myself as a musician, that was the idealistic goal with which we

started out.

I thought that all you had to do was your best and, sooner or later, all

your rewards would come to roost. Again, that isn’t always the case, but for

us it was.

We have squeezed through difficult periods. We have squeaked along without

the benefit of radio and without the benefit of a hit single and without the

benefit of media support.

We started out at the beginning working non-stop and we figured we’ll go out

and play and we’ll be good at that. And that will be the most important

thing. If we get well known as a good live performing band then hopefully

the rest will follow. And for once in modern life, cause and effect did tie

together.

We are now known as a live performing band — which should be the root of

what a musician is — to the point where we can have one record that doesn’t

sell as well as another one and still be able to go out and have a very

successful tour. People know they will be treated to a good performance, to

the very highest standard we can deliver, on any given night. So to have done

it on our own terms is tremendously satisfying.

We were also under a tremendous amount of pressure to compromise, to make

our music more commercial; to write nice little short songs, and to make

them as repetitive and as commercial as possible. Against all that pressure

we have prevailed – adapting the influences we wanted to adapt,

and taking the course in songwriting that we wanted to take – and working

with the people we wanted to work with, on our terms.

It may sound a little egocentric, but it’s not. It’s just dedication to the

values that drew us to music when we were teenagers: we thought that music

was such an honest form of self-expression. And then we went through the

disillusionment of growing up and finding out that it wasn’t that way at all

– but that it was big business and that these musicians were just playing

the music they thought would make them the most money and they were writing

songs that would appeal to the lowest common denominator. They might have

been sniggering behind their bands about the music they were writing, and

laughing at their audience, of whom they were taking advantage. It was very

painful and very difficult for me to become disillusioned. I hope I

weathered it all right, but at the same time it’s part of what’s made me

idealistic about life, but cynical about people.

Alex and Geddy

NK: Does it become more difficult to write each album?

NP: No. I don’t think so. It’s something that we learn more about all the time.

I’ve learned the difference between spontaneity and craftsmanship and there

is a big division. I’ve learned to take advantage of spontaneity whenever

and wherever it happens; even if I have to punch myself in the face to get

out of bed in the middle of the night to write something down, I know at

this point in life, it’s worth it.

Anytime I have an idea, I’ll make sure that I put it down so that when we do

sit down to write an album, I don’t have to dream it all out of thin air. I

don’t have to be creative on the spur of the moment or spontaneously

artistic. I just take advantage of whenever creativity strikes. And we do

record all of this spontaneity on the road.

For instance, during the afternoon soundchecks we often begin with a little

preamble, where somebody will just start playing and everybody will join in.

Depending on the mood of the day, and what you happen to be thinking of at

the time, a lot of interesting things transpire.

At the end of the tour we end up with tape after tape of all these little

things. A lot of it’s just garbage, and some of it is just meandering. But

there are little germs of possibility in there – as well as some moments of

real passion – where you come in with a bad drum mood and just thrash it

out on the drums, and out of that comes an interesting rhythm. Then when it

comes time to record, it’s just craftsmanship.

In the overall view of things, I enjoy the songwriting the most. Because

it’s just us. We just go away together and work very closely and tightly —

and live and breathe new things, new songs and new ideas and possible

directions. I’ll be working on some lyrics while the other guys are working

on some music and after dinner we’ll put them together and a song is

written, and we’ll record it.

We know that when we go away to write songs we should be alone for about

four weeks, and be uninterupted as much as possible. But after four weeks,

we should kick ourselves into the world. We should play some concerts and

shake ourselves up and change mentality towards live performance, just to

get away from the cloistered environment.